I had a really good idea a few weeks ago. I was going to dance, teach dance, and sell brightly-colored spandex thereby reinventing and mastering the concept of a triple threat. I was already doing the first two, and was spending the few minutes before a job interview meandering around a store of overpriced workout attire so I could accomplish the third. The hiring manager rounded up two other hopefuls and led us to an empty table in front of a Nordstrom’s Cafe.

I had a really good idea a few weeks ago. I was going to dance, teach dance, and sell brightly-colored spandex thereby reinventing and mastering the concept of a triple threat. I was already doing the first two, and was spending the few minutes before a job interview meandering around a store of overpriced workout attire so I could accomplish the third. The hiring manager rounded up two other hopefuls and led us to an empty table in front of a Nordstrom’s Cafe.

“Did you know this was going to be a group interview?” one of them asked quietly. “I had no idea,” she said. “But maybe we’ll all get hired together.”

“That would be so cool.” The other girl said. I smiled and nodded wondering just how many positions there were to be filled.

“So this is a super casual interview,” the manager said smiling. “As you guys probably know we are all about helping all types of women. We really want every woman to feel comfortable from the outside in, and we just want to get to know and figure out where you’d fit within the company. So just go ahead and introduce yourself and just tell us why you want to work here.”

That is a question I have always hated. "I like to eat food, and my landlord won't let me pay him in experience and bragging rights," though perfectly true, isn’t exactly the answer potential employers want to hear.

During a mock group interview, in college, the presenter posed a question, “If you could be any type of tree what kind would you be and why?”

"I'd be a Christmas tree,” I said, “because it's a symbol that represents a time of year that makes a lot of people happy regardless of whether celebrate the actual holiday."

The boy next to me answered, “I’d be a carrot tree because I’m unlike other you’ve ever seen.” He was pleased with himself, and the workshop leader thought his answer was memorable and clever. I disagreed. The reason you have never seen a carrot tree is because carrots do not grow on trees, and if they did it would be an entirely different plant. The fact that he didn’t know this mean that he either did not absorb or retain information or didn’t eat vegetables which would result in a host of health problems and neither of those things would be very useful to the company.

That, however, is the type of thing we do in those situations. We try to be remembered and impressive. We paint a picture of ourselves that adheres to what we think people want to see. I’d argue that one of the most detrimental things you can do in an interview is believe them when they say, “We want to see that real you.” In most cases, what they really want is to see if you fit into the strangely snapped box they created before they knew that you ever existed. And we want to fit. No one seems to grow out of the elementary school need to fit in with the kids who have what we don’t, and so, like the line of dancers, in the musical, A Chorus Line, we step-kick-kick and smile on cue all while singing “I really need this job. Please, God, I need this job. I’ve got to get this job!”

“Tell us about a time when you received great customer service at. It can be at any store. It doesn’t have to be here," said the manager.

“Starbucks,” I said, automatically. I told them how the baristas knew my name, would notice when I hadn’t been in for a while, and how they knew that something was wrong when I ordered a white mocha. “I know they aren’t my friends,” I said, “but I would go out of my way to go to that Starbucks because it felt like they knew me.”

The other girls nodded and hummed, and then they proceeded to say that they loved shopping at the very establishment that had gathered us together that afternoon for an interview. As an explanation, they both offered individualized versions of what sounded to me like “Blah blah blah blah blah bloppity bloopity bloop bloop.” The manager applauded the other applicants for their answers and said how their experiences were really what the company was about, “We just want to help each person find that one item of clothing that makes them feel beautiful on the outside so they can start to make changes on the inside.”

I felt so betrayed and annoyed, naming the company you are interviewing for as your favorite store is the equivalent of reminding your teacher that he forgot to give you homework. It is sucking up 101. It is deplorable behavior that warrants being ignored at recess, and for the life of me, I cannot tell you why I didn't do it.

In the introduction of Neil Gaiman’s Trigger Warnings: Fictions and Disturbances, he writes, “I find myself, at the start of each flight, meditating and pondering the wisdom offered by the flight attendants as if it were a koan, or a tiny parable, or the high point of all wisdom.” With a mother as a flight attendant and the Philadelphia International Airport on my list favorite places I grew up hearing the pre-flight instructions, but until that moment they had never been about more than oxygen. Secure your own mask before helping others. “I think about the need to help others,” Gaiman writes, "and how we mask ourselves to do it and how unmasking makes us vulnerable.” He goes on to describe people who “trade fictions for a living.” He was talking about authors, but sitting in the group interview answering questions that aimed to prove that I would be of some value to this national corporation, I’m pretty sure everyone does it.

The manager rolled our applications into a tube and shoved them into the pocket of her jacket. “It was nice to meet you girls.We will call you by Monday if we have a place for you.” Instead of walking back to my car, I rode up the escalator and walked to Starbucks.

“Hey!” the barista said pulling out sharpie and preparing to mark the familiar green and white cup. “What are we doing for you today?”

“Hi,” I said, “Can I have a grande white mocha, please?” he nodded, scanned my phone, and told my drink would be ready soon. When the cup came, I took a swig. On the white lid was the shape of my mouth printed in a wine-colored shade of lipgloss called "Desire." I took another sip and sighed.

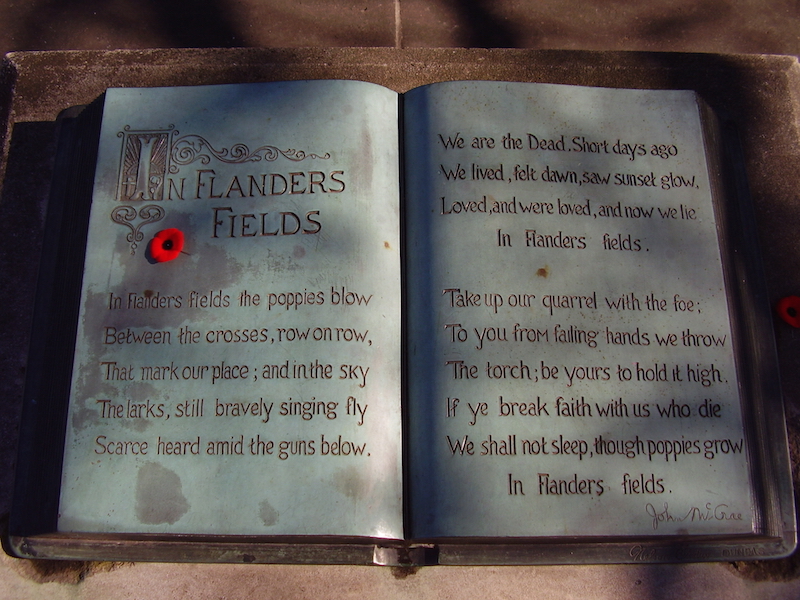

“Christ likes us to prefer truth to him because, before being Christ, he is truth. If one turns aside from him to go toward the truth, one will not go far before falling into his arms.”

— Simone Weil

“Christ likes us to prefer truth to him because, before being Christ, he is truth. If one turns aside from him to go toward the truth, one will not go far before falling into his arms.”

— Simone Weil