How to Know

Tom Sturch

"Knowing is the responsible human struggle to rely on clues to focus on a coherent pattern and submit to its reality." —Esther Lightcap Meek, Longing To Know

"Knowing is the responsible human struggle to rely on clues to focus on a coherent pattern and submit to its reality." —Esther Lightcap Meek, Longing To Know

We were in the car going somewhere. Our children, Joseph and Jonathan were in the back seat with Bev and me up front. It was nearly Christmas and Joseph was challenging the veracity of our assertions about Santa Claus. It's you guys, right? Bev and I weren't ready to abet our seven-year-old's descent into the murky realm of fact versus fantasy. It's a yes or a no, he insisted. Stunned by his need for this knowledge, the best I could do was offer a pathetic, Um, well... yes and no.

I still struggle with this. I would love to be certain, but I know that real truth resists the either/or of certainty. And though I'm a big fan of both/and quantum outcomes, this seems equally unsatisfying. Besides, there are no Hallmark moments reading quantum mechanics to your kid at bedtime.

I am not alone. The struggle is historic. Duality is expressed in the Age of Enlightenment from the 18th century still evidenced in the sacred/secular divide. It's in ancient Greek philosophy, in Raphael's School of Athens showing Plato's upward pointing finger and Aristotle's downward palm as essence and existence at odds. We even see its beginnings in the torrents of creation: the cold and the heat, high and low pressures, tectonic forces, the things we're made of. It seems the world's dynamics—its mechanisms for change—depend on apparent opposites cast irreducibly together. Yet, can such a maelstrom be the unity we intuit?

Duality inheres a two-ness that begs for a reconciliation that is beyond our present choices. We sense it should be there on the insistence of our desire alone—a belief that persists in a search for justification that is fleeting. So the choice seems between an endless struggle and the sidelines—between living in the tension-filled room where money, power and influence too often win, or being alienated by skepticism that leads to desperation.

Poet William Bronk offers an example of the latter position. Michael Heller remarks in the New York Times Book Review, “The natural world, Bronk would insist, is a world we can never know.” Bronk’s work suggests a basic estrangement between man and nature, promoting a bleak human situation we persist unsuccessfully in belonging to. Consider his poem On Being Together:

I watch how beautifully two trees stand together; one against one. Not touching. Not awareness. But we would try these. We are always wrong.

But consider the struggle again. In the Four Corners region of New Mexico, in Chaco Canyon, are the ruins of an ancient pueblo village of the Anasazi Indians. For years archaeologists puzzled over its disparate buildings, spiral petroglyphs and stone slab arrangements. Finally in 1979, a team oriented parts of its layout on the sun and suddenly, the pueblos became a watchport on the seasons. Their strange architecture was a finely tuned eye on the relationship of the earth with the stars. Here is human endeavor, book-ended in time, following human longing for harmony, clarity and insight. The patterns are there.

How we know is captured in a context somewhere between the rules and the world where our selves are subject to both, and certain of neither. But in this proximate humiliation our beliefs can flourish in the apprehension of patterns—our coming to know by glimpses on the hope that our home is secure in the stars.

Joseph is twenty-seven, now. I don't think he has reached a conclusion on the matter of Santa Claus. I think he is beginning to rest in the dialectical tension of life. He still wants concrete answers on metaphysical realities, but all I can do is give him two trees—not Bronk's—but rather one on the earth pointing to the sky that is also a similitude of the one that gives hope. In the mean time he has become one of the best Santas I know.

This fall, I plan to take my twelve-year old pheasant hunting for the first time, as my father took me. Last fall, when he was eleven, I took Micah out to shoot in a gravel pit outside of town, after which time I had one question:

This fall, I plan to take my twelve-year old pheasant hunting for the first time, as my father took me. Last fall, when he was eleven, I took Micah out to shoot in a gravel pit outside of town, after which time I had one question:

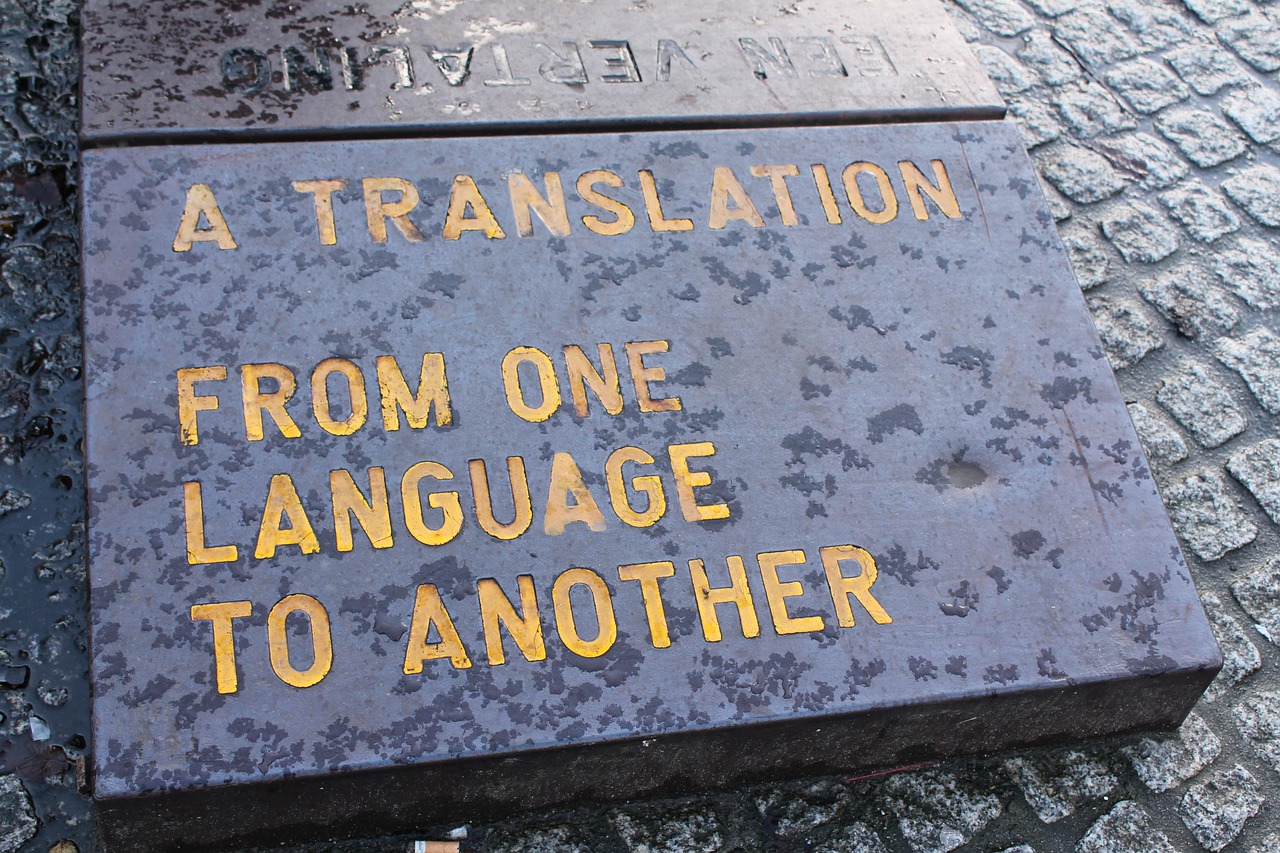

The documents are in folders, carefully taken out and laid upon my desk. Others have been folded and refolded; the creases have become a part of the paper. They are birth and marriage and death certificates, transcripts and diplomas. I scan the documents and send the file to one of my translators. After a few hours or days, the translated words in English are sent back. I look through, edit and check. The documents are filled with words like certify, signature, official, issued, expire; it’s pretty straightforward stuff.

The documents are in folders, carefully taken out and laid upon my desk. Others have been folded and refolded; the creases have become a part of the paper. They are birth and marriage and death certificates, transcripts and diplomas. I scan the documents and send the file to one of my translators. After a few hours or days, the translated words in English are sent back. I look through, edit and check. The documents are filled with words like certify, signature, official, issued, expire; it’s pretty straightforward stuff.  As holidays with my extended family arrive, so does the expectation of playing games. Whether in a pool, in the snow, in a gym, on the floor of a living room, or, especially, at the table. Ah! The evening table game. We’ve played everything from “Awkward Family Photos” to “Risk” to “Tenzi” to “Reverse Charades” to the incredible, mind-bending card game “Killer Bunnies”.

As holidays with my extended family arrive, so does the expectation of playing games. Whether in a pool, in the snow, in a gym, on the floor of a living room, or, especially, at the table. Ah! The evening table game. We’ve played everything from “Awkward Family Photos” to “Risk” to “Tenzi” to “Reverse Charades” to the incredible, mind-bending card game “Killer Bunnies”. The grammarian

The grammarian  It can’t make sense everywhere. I assume it has a temperate climate bias. Or, to be more precise, a four-season climate bias, yet it’s arguably one of the most lasting pieces of colloquial insight bequeathed to us from the recent past: “March comes in like a lion and goes out like lamb.” Or vice versa. That’s the allure of the phrase, I think, its seesaw mechanics. Pay attention to this one month, this little adage promises us, and you too can predict the weather. It’s tempting to make weather simple. The weather in any given place is distillable to a few features, to northeasters and lake-effect snow and Santa Ana winds. Where I live, any given day is likely to be ruined by wind, first and foremost from the northwest, straight out the arctic, and second from dead south, straight out the furnaces of hell.

It can’t make sense everywhere. I assume it has a temperate climate bias. Or, to be more precise, a four-season climate bias, yet it’s arguably one of the most lasting pieces of colloquial insight bequeathed to us from the recent past: “March comes in like a lion and goes out like lamb.” Or vice versa. That’s the allure of the phrase, I think, its seesaw mechanics. Pay attention to this one month, this little adage promises us, and you too can predict the weather. It’s tempting to make weather simple. The weather in any given place is distillable to a few features, to northeasters and lake-effect snow and Santa Ana winds. Where I live, any given day is likely to be ruined by wind, first and foremost from the northwest, straight out the arctic, and second from dead south, straight out the furnaces of hell.

![Photo by Sara Reid - Flick [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://static1.squarespace.com/static/5898e29c725e25e7132d5a5a/58aa11bc9656ca13c4524c68/58aa12179656ca13c4525dcd/1487540759619/3599597595_1d64cae554_z.jpg?format=original)

I always try to pick just the right moment to tell people. That moment is sometime between realizing that they are one of those who will need to know, and the point when they figure it out on their own. Although I frequently share intimate details of my life, in writing, and with my bank teller, or a new acquaintance, there is one thing that I hold back until the last minute.

I always try to pick just the right moment to tell people. That moment is sometime between realizing that they are one of those who will need to know, and the point when they figure it out on their own. Although I frequently share intimate details of my life, in writing, and with my bank teller, or a new acquaintance, there is one thing that I hold back until the last minute.

The story was told to me with flannelgraph figures that effortlessly hopped from one point on flannel to the next. Abraham figured that it was time to find a wife for his son, so he sent his servant back to the old neighborhood to find a wife who had home-training similar to his own son’s. The servant prayed that the right girl for his master’s son would make herself known by giving water to him, his team and all of their camels. The servant made several turns that led him to Rebekah. He asked her for a drink water, and she gave it to him, and offered to get water for his team and their camels until they weren’t thirsty. This was a story about asking God for help with big decisions.

The story was told to me with flannelgraph figures that effortlessly hopped from one point on flannel to the next. Abraham figured that it was time to find a wife for his son, so he sent his servant back to the old neighborhood to find a wife who had home-training similar to his own son’s. The servant prayed that the right girl for his master’s son would make herself known by giving water to him, his team and all of their camels. The servant made several turns that led him to Rebekah. He asked her for a drink water, and she gave it to him, and offered to get water for his team and their camels until they weren’t thirsty. This was a story about asking God for help with big decisions.