. . . for my dad, Daniel Bowman, Sr.

. . . for my dad, Daniel Bowman, Sr.

“Baseball, it is said, is only a game. True. And the Grand Canyon is only a hole in Arizona.”

― George F. Will

The dog days of summer are just around the corner, and I’m thinking about baseball. Anyone who’s been around the game knows that it has long been considered a metaphor for life, or a metaphor for America, or a metaphor for…something. The daily grind, the peaks and valleys of success and failure: the rhythms of baseball reflect our experience.

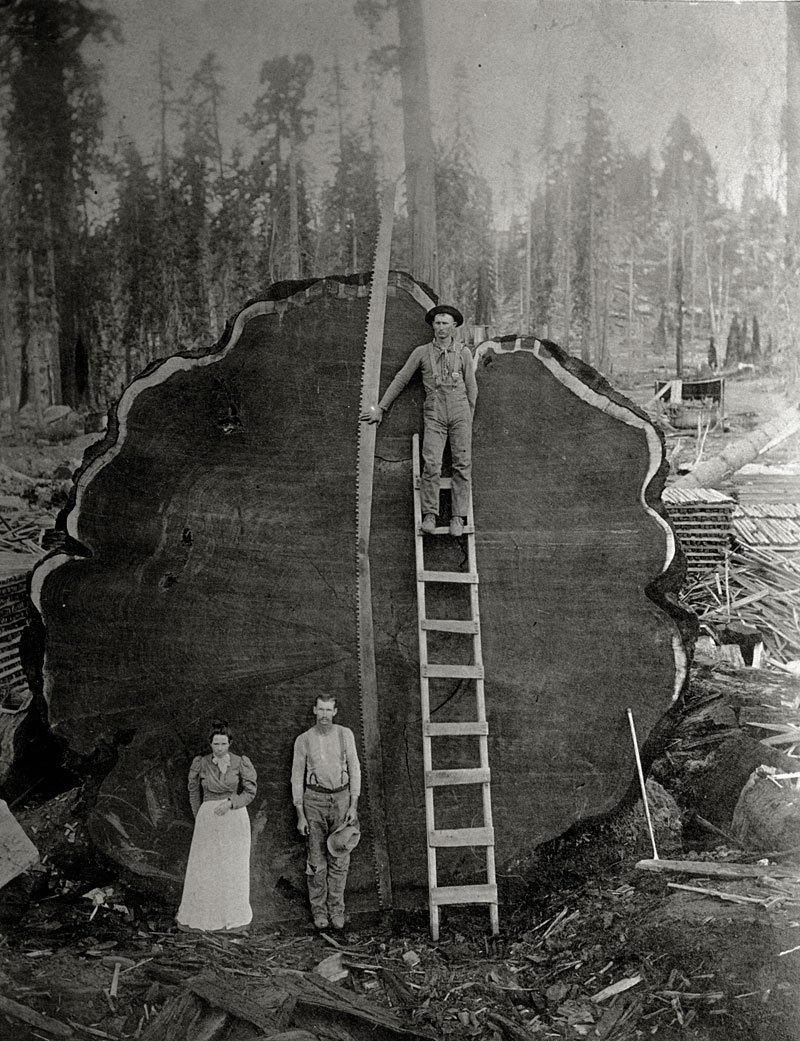

At the big league level, we put our faith in larger-than-life heroes who can change the fate of the team with one swing of the bat, or streak across the field in a display of elite athleticism available only to a few. And for his trouble, the worst player on the worst MLB team, in today’s high-stakes sports world, is making the kind of money that none of us will ever see in our lifetimes.

As a native New Yorker, I grew up a Yankees fan, and I still love and follow major league baseball. But as I get older, I think back to the games my dad took me to when I was a kid: Single-A New York-Penn League games. All over again, I’ve become enamored of the minor leagues, where baseball and its attendant metaphors play out in different ways. The towns aren’t glamorous; the fields, though nice, are not obsessively manicured. The players—and their salaries—are not larger than life. They feel more like me, my family, my friends and neighbors.

In recent years, when I lived in western New York, I often made the trek to the humble baseball town of Batavia, home of the Single-A, short season Muckdogs, an affiliate of the St. Louis Cardinals. Dwyer Stadium in Batavia seats 2,600, making it one of the smallest of the hundreds of minor league venues around the US and Canada.

Some MLB stars have passed through Batavia in recent years. No doubt a few more will have a stint there en route to the Bigs, giving the locals a brush with greatness, a story to share.

But the proud list of Muckdog alums who’ve made it to the majors is not, to me, the most interesting aspect of minor league baseball. I love to show up early (parking is easy and affordable!) to see the ambitious young players, either just out of college or sometimes just out of high school, taking batting practice. These kids were just recently drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals, a legendary franchise with the most World Series titles of any club in the National League. With a six-dollar ticket, you can get right up on the dugout; you can see the determination and naïveté on their faces. They are playing their first professional games. They are beginning a journey.

Somewhere on the bench (especially when you’re at a double- or triple-A game), there’s a guy who just turned thirty, which is ancient in professional sports years. He was a winner, a champion and record-holder in high school and college, and a sure-thing to breeze through the minors on his way to a multi-million dollar big league contract. But something happened. He hurt his knee. He couldn’t hit the curveball. Or worse: there was no single factor to blame. He just didn’t pan out. He’s not fooling himself any longer; he knows he missed his chance at fame and millions. But he stays on the club because he still has something left to offer on the field. And he’s starting to get a kick out the fact that the young kids look up to him as a veteran leader in the clubhouse.

Those aren’t the only two kinds of players in the minors. There’s everyone else, everyone in between whose names won’t be remembered, people at every stage of the journey. All of us. Truly, with the cheap tickets and intimate ballparks, there’s very little separating us from them—both literally and metaphorically. It’s a quest narrative for the players, and for fans as well. Whether we’re young with stars in our eyes, older and wiser, or somewhere in the vast middle space; whether we had our best day or a terrible outing we’d rather forget…we’ll all get up tomorrow and do it again.

Corny? Yes. But one of these days, go sit on the hard bleachers at the local minor league park with friends and neighbors, eat a hot dog, and see the next batter step up to the plate. Feel that little thrill: the enchantment of possibility. Let it get inside you. This might be the night. Watch him connect, blast the tiny sphere right over their heads.

And when you jump up and cheer, don’t tell me it’s only for the players on the field. It’s for all of us.