The 59th

William Coleman

In the fall of 2000, as part of my work for a literary magazine in Boston, I visited William Meredith in the home he shared with his partner, Richard Harteis, in a wooded community near Uncasville, Connecticut.

Nearly two decades earlier, at sixty-four, Meredith had suffered a stroke that had immobilized him for two years. As he recovered, it was found that he had expressive aphasia, a condition that arrests the ability to render into words what one perceives or thinks. Until then, William Meredith had made his living as a teacher and as a writer. He was Poet Laureate of the United States from 1978 to 1980.

Before we went inside, Richard showed me the view from their back yard. He said that he and William had been working on writing haiku. One image at a time, he said.

When I finally met Mr. Meredith, he was still in his bathrobe, eating cereal. I was early. He told me so. Then he told me to sit down.

There at the kitchen table, I asked my questions—veiled versions of "How should I live? How should I write?"

With each one, he watched me acutely, and then disappeared as he grappled toward utterance. "A good man," I remember him telling me over the course of half a minute, "is a useful man."

The first poem of his I ever read was called "Poem." My teacher, Albert Goldbarth, had handed copies of it around the workshop table one evening, and read it aloud to us.

The immaculate, stately phrasing of the first stanza immediately compelled me. I knew at once that those words were committed to my memory:

Poem

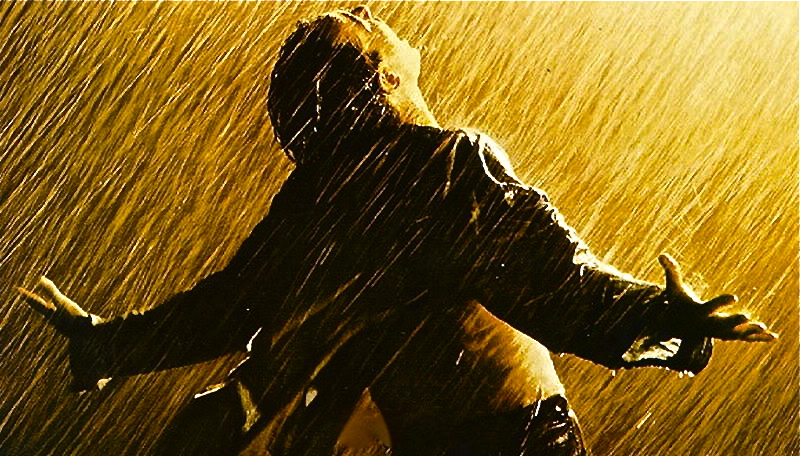

The swans on the river, a great

flotilla in the afternoon sun

in October again.

In a fantasy, Yeats saw himself appear

to Maud Gonne as a swan,

his plumage fanning his desire.

One October at Coole Park

he counted fifty-nine wild swans.

He flushed them into a legend.

Lover by lover is how he said they flew,

but one of them must have been without a mate.

Why did he not observe that?

We talk about Zeus and Leda and Yeats

as if they were real people, we identify constellations

as if they were drawn on the night.

Cygnus and Castor & Pollux

are only ways of looking at

scatterings of starry matter,

a god putting on swan-flesh

to enter a mortal girl

is only a way of looking at love-trouble.

The violence and calm of these big fowl!

When I am not with you

I am always the fifty-ninth.

In the years to come, I would see the justice of the poem's title, how the work gathers much of what is essential to his work as a whole: public speech about private matter, arising from kinship and deep reverence clarified by strict observance.

Daniel Tobin, in an essay in the Yeats/Eliot Journal in the summer of 1993, notes that for Yeats, "Man was nothing... until he was wedded to an image…Still, it took him many years of arduous labor…to realize fully personal utterance in his poetry."

Yeats was fifty-two when he imagined in Coole Park that he was wedded to a lone swan that would, with all the rest, one day fly from him, to build life on another's waters.

The desolation of his imagining that his imagination would one day disappear is of the kind Tobias Wolff describes for Mary in his short story "In The Garden of the North American Martyrs," when she finds that the words for her thoughts "grew faint as time went on; without quite disappearing, they shrank to remote, nervous points, like birds flying away."

Yeats died in 1939. Meredith wrote his poem in 1980.

Before Richard turned to open the glass door of the kitchen, he followed where my gaze had long since alighted. He lamented the power plant that had been built on the far banks. But the power plant was not visible to me. For there, on the river, were the swans.