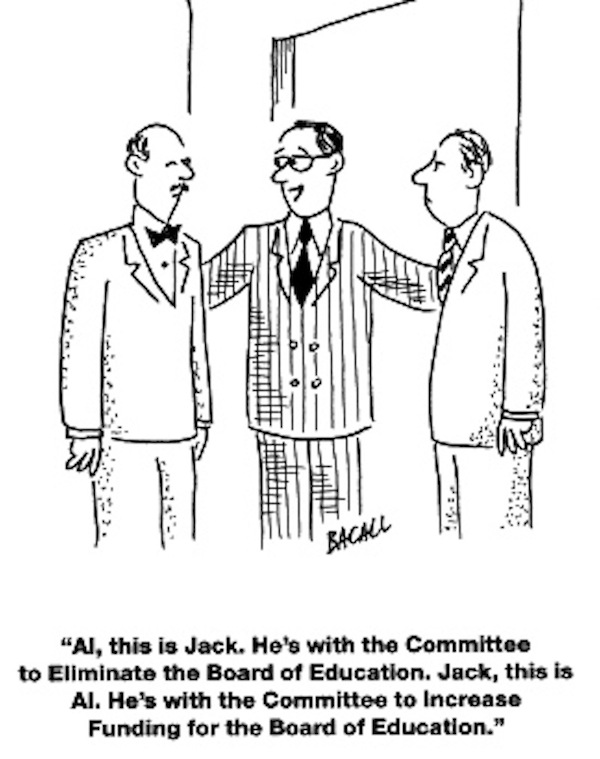

Introductions

Drew Trotter

"Joe"? "Just call me Joe"? As if you were one of those stupid 22-year old girls with no last name? "Hi, I'm Kimberly!" "Hi, I'm Janice!" Don't they know you're supposed to have a last name? It's like they're an entire generation of cocktail waitresses. ~ You've Got Mail by Nora Ephron

"Joe"? "Just call me Joe"? As if you were one of those stupid 22-year old girls with no last name? "Hi, I'm Kimberly!" "Hi, I'm Janice!" Don't they know you're supposed to have a last name? It's like they're an entire generation of cocktail waitresses. ~ You've Got Mail by Nora Ephron

I consider myself a practical man, and I know that God knows everyone’s name and that I don’t. I even know that I have forgotten, and will forget, the vast majority of names of the people to whom I have been, and will be, introduced in my life.

That does not change the fact that I am saddened, and even a little offended, every time I meet someone who only gives me their first name. I know they are trying to be nice to me. In my old age especially, they are trying not to load me down with too much information, wanting to help me remember their name so I won’t be embarrassed later in the conversation, when I can’t remember it. I know all that. I get it.

What is lost in that bargain, though, is something of what an “introduction” is supposed to be. The word comes from two Latin words, which, etymologically mean “to lead one inside”, i.e. to bring someone into a place from outside the place they presently occupy. If we pursue that idea to its fullest, an introduction takes the person to whom we are “introducing” ourselves by the hand, leading them into our life, into our house.

When you tell me you are “Clem” and don’t tell me you are “Clem Kadiddlehopper,” you are telling me one of several possible things. The kindest is that you really are open to me as a person, and you are opening yourself up to me as one, too. We are immediately on a “first-name basis”. You are not putting any boundaries on our conversation; you have not pre-judged me or what friendship we might develop. You actually are “introducing” me into your life.

I am sure in the vast majority of cases, this is what is meant by Christian-name-only introductions. But lurking in every introduction of that type, I believe, is a certain distancing, rather than embracing. Perhaps a quick, first-name introduction is part of our modern penchant to get to the point as rapidly as possible. Perhaps it has something to do with our distaste for formality, and the perception that stating the last name is to distance oneself from the other.

I believe a first-name-only introduction performs just the opposite. I believe it says to the other: “I don’t want you to know me too well, to know my history, my family. I just want you to put me in a nice, safe, generic group of Georges or Marys, all undifferentiated, all combined in one great human soup. Please stand back; I don’t want you to get to know me too ‘up close and personal.’”

Or it’s saying something worse. It’s saying, “I am nothing more than a generic, existential George or Mary. I have no past, no future. I am simply me, and I am nothing. Pay no attention to me, and, please, forget me as soon as we separate from one another.” None of us wish to go down that path with anyone.

Please, at least when you meet me for the first time, let me know your full name. We’ll get to a real first-name basis a lot more easily if you do.