Different Roads to To Kill a Mockingbird (Part 2)

Callie Feyen

It seems though, that To Kill a Mockingbird is the sort of book that gives something to me every time I return to it. This year, it’s Bob Ewell I’m paying attention to, though I hadn’t planned on taking a closer look at him.

It seems though, that To Kill a Mockingbird is the sort of book that gives something to me every time I return to it. This year, it’s Bob Ewell I’m paying attention to, though I hadn’t planned on taking a closer look at him.

My drive to school these days isn’t terribly interesting. It’s mostly highway driving, and save for the leaves that bloom with color in the fall, there’s not much to look at. I feel more that I am driving away from something, then towards it. I am a mother now, to Hadley and Harper, and I haven’t gotten used to the fact that the three of us fumble through most of our days separately, when just a while ago we did it together. I know once I start teaching, once I see my students, I’ll step into a role I love. Teaching awakens a side of me that is vibrant and bold and I love that gal when she comes out. But every day I begin my commute, I ache a little.

So I think about Bob Ewell, and it occurs to me that he and Atticus Finch have something in common: both of these men have wives who died. We don’t know how they died, and we don’t know how Atticus and Bob mourned; perhaps they are still mourning when we meet them. I press my foot to the accelerator because I can’t wait to point this out to my students. What will they think about Bob now? What will they do with this information?

In the classroom, I write “Atticus Finch,” and “Bob Ewell” on the board in a Venn diagram, and ask my students to do the same on pieces of notebook paper. “lawyer,” “educated,” “takes care of his kids,” on one side and “drunk,” “illiterate,” and “beats his kids,” on the other. “White,” and “male,” are in the center.

“What else?” I ask, tapping the whiteboard.

“One’s good, one’s bad?” a student suggests.

“OK, but they have something else in common.”

The kids look at me in disgust at first, but I wait and one says, “They don’t have wives!”

“Yes!” I say.

“Because they’re both dead!” one exclaims.

“Atticus and Bob are dead?” another one, who is confused, asks.

“No! Their wives! They died!” three or four say in unison.

We are so excited about this realization, and I don’t believe it’s because we’re relieved that Bob had a bad thing happen to him. I think we’re pleased because we might’ve discovered another layer to him.

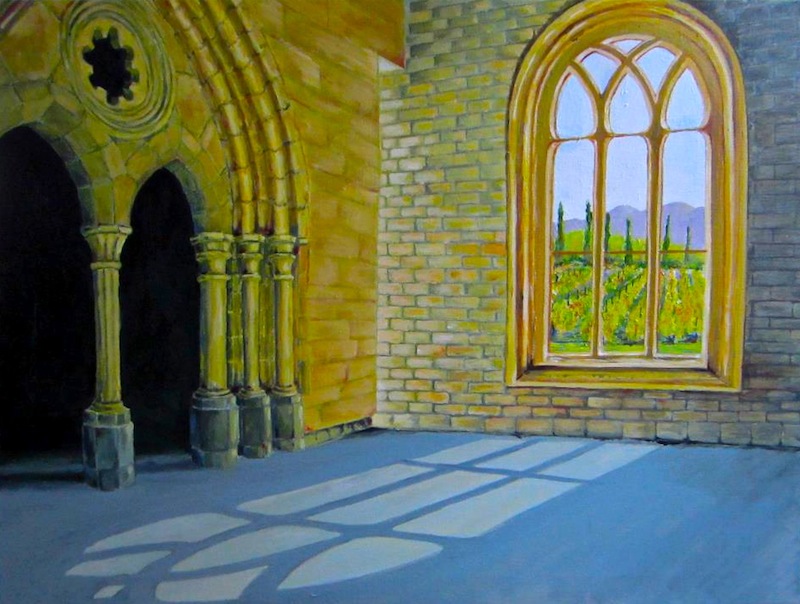

“Maybe he wasn’t always like this, you guys,” I say, pointing to the word, “drunk” on the board. The class is shiftless and silent—a sure sign they are captivated. I take this as a miracle I must not waste and dive in.

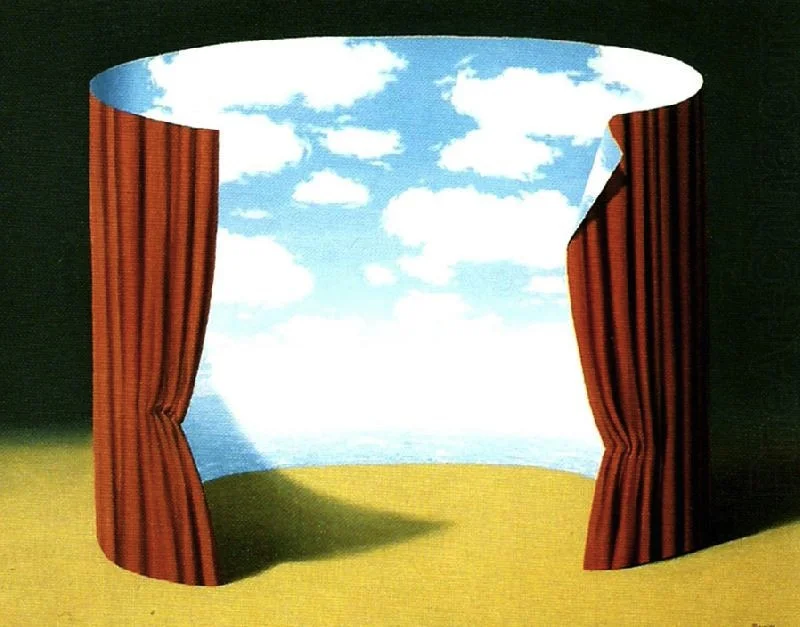

“What do you think Bob’s wife was like? Do you think they had a love story? Do you think he has any good memories?”

I ask everyone to get out another piece of paper. I tell them to write as though they are Bob Ewell. “What else can you say about him that goes beyond racist, ignorant, and negligent? What happens when you look at him as a human that was wonderfully and fearfully made?” And then I whisper because I’m afraid to say it: “Bob Ewell has been made in the image of God.” Their eyes dart up from their papers. Fifteen wide-eyed adolescents look at me and I wonder if I’ve gone too far.

A few years ago I pulled a similar stunt with 8th graders. I suggested to them that maybe Judas had been forgiven. Maybe God could do that. The next day an infuriated mother walked into my classroom and screamed, “Judas is in hell! He’s in hell!” I shutter at the memory but continue with my experiment. “Go ahead and write,” I tell my students. “Let’s see what you come up with.”

“I am thinkin’ ‘bout my wife again,” one student writes. “I wish she could make her famous cornbread pancakes. I wish I could stop drinkin’.”

Another writes to Bob’s dead wife. “I don’t know why I write you these letters and bury them by your grave, but it makes me feel better. Every time I look at our children, Mayella especially, I feel an anger. I don’t know where it comes from but it consumes me. Mayella grows beautiful and strong, and she reminds me of you every time I see her.”

Some students reflect on Atticus: “Me and Atticus lived in the same neighborhood. We weren’t friends, though. I was jealous of him because he went to school. I always wanted to learn new things but my parents didn’t have time to teach me. Plus, they would be fighting every day.”

One wrote about Bob fishing as a young boy when his father was off at the bar, drinking. “Those were the best days,” he writes, “Sam and I would always jump in the pond and swim around.”

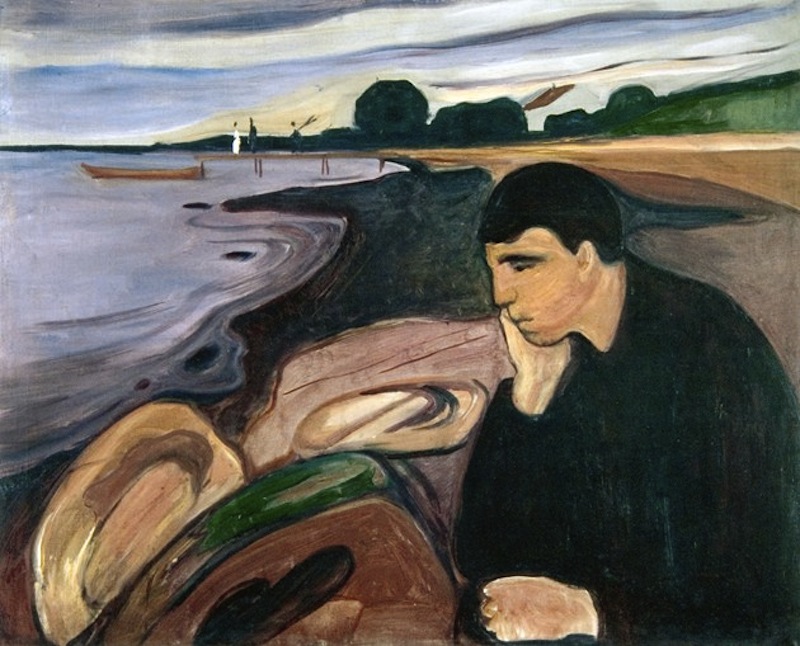

The class is subdued when they finish writing. There’s a feeling of confusion while they pack up and get ready to head home. I think they’re in the thick of wonder—when wonder is dark and mysterious. I hope I’ve introduced them to the real work of writing.

But as I drive home, I begin to second-guess myself. Was I wrong to encourage my students to imagine there is more to Bob Ewell than what we read in To Kill a Mockingbird? Should I have waited for his final murderous intention in the woods before I had the kids evaluate him? Have I set them up?