A Space of One’s Own

Howard Schaap

“Been doing any writing?” my sister asked me at Thanksgiving.

“Been doing any writing?” my sister asked me at Thanksgiving.

“No.”

“How does that make you feel?”

“Psychotic.”

I should have said, of course, “Hyperbolic and clichéd,” since I’m not feeling exactly psychotic, but more like imbalanced or disoriented—like when you wake in the dark and don’t know where you are. And the cliché: “I need to find time to write,” says every writer in the world.

But for me it’s actually more akin to finding space to write. The best writing I’ve done this fall, I confessed to a writing friend, was during my commute. “Confessed,” because doing it was dangerous bordering on reckless, even when I qualify this confession by noting that I meet perhaps five cars during a forty-five minute stretch of my drive.

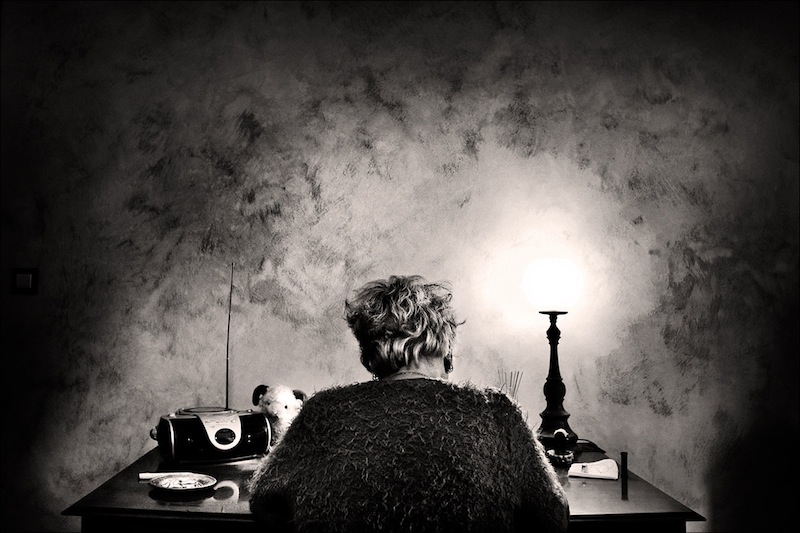

More pertinent to why I write then is that space opens up then. Sometime after the stop sign in the unincorporated town of Kenneth, with the bar that will have eight cars parked out front in the evening. Typically after the descent into the long valley of Champepedan Creek with the ghostly cottonwood, its long arms stretched above its head to bless the creek pasture and its cattle. Sometime after the midway point of a ten-mile flatland, marked by three cottonwoods grown up as sisters in a touchless dance. Before the road bends in deference to the next river, the Kanaranzi, which is said to mean in Dakota, “where the Kansas were killed.” Somewhere in this space, inspiration—or at least the deep, irresistible impulse to write—comes upon me.

And I do write, right or not, and drive with my knee.

I know when Virginia Woolf wrote A Room of One's Own, she had something a little different than this in mind, but my commute reminds me that a writer needs a space of one’s own, that time when the quotidian recedes or, conversely, coalesces into a present that launches writing. One of these spaces, in a semester of chaos, happens to be my commute.

Another one of these spaces, a better one, though not necessarily safer depending on what kind of God one might meet there, is a worship service. Amongst the words of scripture, catechism, and hymn; lost in the long prayer, in the wonderful interminable sermon. Then, too, I find myself in a space of my own with something lurking in the spaces between the words and all those rapt consciousnesses. Then, too, things come clear, words suggest themselves and I make notes madly along the edge of the bulletin. I would stay in that moment because something has opened up—a where and a when, a place and a time, a space.

We would do well to cultivate such spaces, but also take them where we find them.

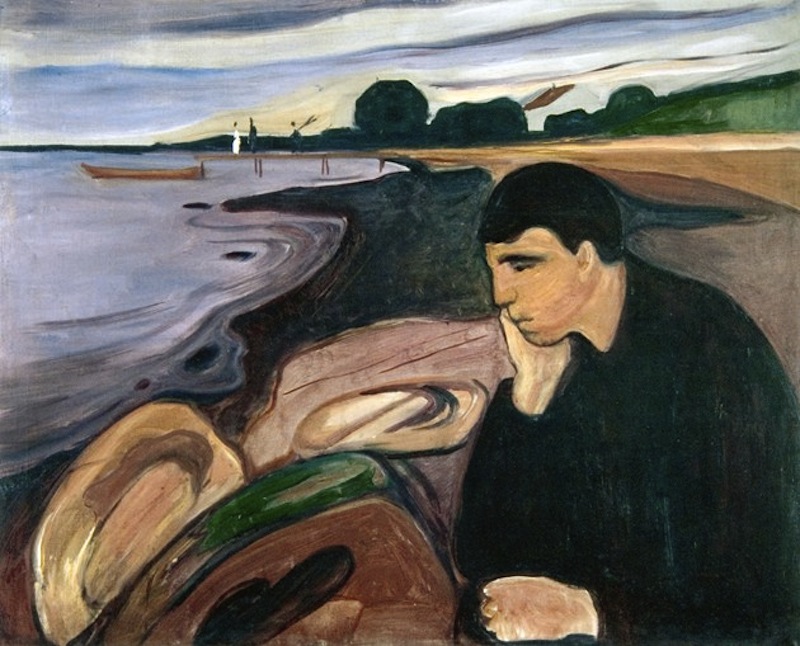

(Painting by Edvard Munch)