“I thought therapy was going to clear up the fucking freak show in his head.”

—Carmela Soprano

“I thought therapy was going to clear up the fucking freak show in his head.”

—Carmela Soprano

In The Sopranos, Tony Soprano and his wife, Carmela, spar over differences, but they’re largely united in their delusions about Tony’s line of work. Tony believes he is a “soldier” carrying out orders—sordid, illegal, it doesn’t matter—for the good of the mob Family. And he does. Not always unflinchingly, but unfailingly.

Carmela’s delusions center on the home front. She convinces herself that her place is at Tony’s side. Usually Tony’s business rarely troubles the waters of Carmela and their children’s lives (Meadow and A.J.). But when mafia blood seeps under the door, Carmela is reminded of the high stakes she gambles to ignore. She sometimes wrestles about staying with Tony, but in spite of the dubious origins of the guns and piles of money hidden in the ceiling tiles; despite increasing number of Family disappearances, she stays.

In fact, for a while she is church sanctioned to remain in the marriage. When Carmela seeks the counsel of the well-meaning family priest, he encourages her to help Tony be a better person.

Carmela overlooks Tony’s philandering, telling herself the women mean nothing to him. But when one calls their home looking for Tony and A.J. answers the phone, Carmela is incensed. Only as it crosses her threshold does she feel the threat of Tony’s infidelity.

This breaching of her walled fortress spikes internal turmoil, and she seeks out a therapist. He catches on quickly to the delicate way she frames her husband’s work, and knows instantly what it says about her.

Carmela: His crimes … they are … organized crime.

Dr. Krakower: The mafia.

Carmela: (Gasps) Oh Jesus. Oh, so what. So what. He betrays me, every week with these whores.

Dr. Krakower: Probably the least of his misdeeds.

Carmela becomes defensive when the therapist labels her an accomplice to her husband’s crimes, telling him, “All I do is make sure he’s got clean clothes in his closet and dinner on his table.”

Her love of money competes with her love of family. She doesn’t see how being an accomplice to Tony has created blindness in her children. Meadow becomes a high salaried attorney defending white collar criminals. Tony seems set to help A.J. reach his dream of opening his own nightclub, which could easily be the next mob front like Bada Bing.

Carmela’s denial is haunting. Haunting like the crosses that are all around her, on her necklace, on the walls of her home, in the church she frequents. They are everywhere as in Flannery O’Connor’s “Christ haunted South,” where Jesus is invoked but not followed.

She has moments of spiritual clarity, like when Christopher nearly dies and she intercedes for him and her family. “Tonight I ask you take my sins and the sins of my family into your merciful heart. We have chosen this life in full awareness of the consequences of our sins.” But her vision clouds again, and later she asks Tony to put extra pressure on the building inspector so she can move forward on her spec house, knowing full well what that type of pressure implies.

Carmela whitewashes Tony’s career because of what she gains from it. In his poem “Moby Dick,” Dan Beachy-Quick writes:

You beat your head against the jagged rocks.

Blind in depths so dark light itself is blind,

You knock your head against the rocks to see

And scratch the god-itch from your thoughts.

We can hope Tony’s gestures of forgiveness and compassion at the end of the show signal a new direction for the Sopranos. But if they don’t, the last scene, when they gather at their favorite restaurant, is chilling if it marks only the perpetuating of a mafia family status quo.

My sister and I used to have picnics in our family garden and study Greek Mythology.

My sister and I used to have picnics in our family garden and study Greek Mythology.

I was in a porn film. The previous sentence is actually factually incorrect, but it’s an attention grabbing introductory line, right? Where substance doesn’t grab us, spectacle usually does the trick. I seem to recall coming across a

I was in a porn film. The previous sentence is actually factually incorrect, but it’s an attention grabbing introductory line, right? Where substance doesn’t grab us, spectacle usually does the trick. I seem to recall coming across a

I’m starting to get it. The spirituality of baseball. The miraculous has happened: the Cubs have won the World Series.

I’m starting to get it. The spirituality of baseball. The miraculous has happened: the Cubs have won the World Series. Out of all the treasures in the Book of Common Prayer, to me chief among them are the collects, the compendium of short and beautiful prayers, and chief among these is The Collect for Purity:

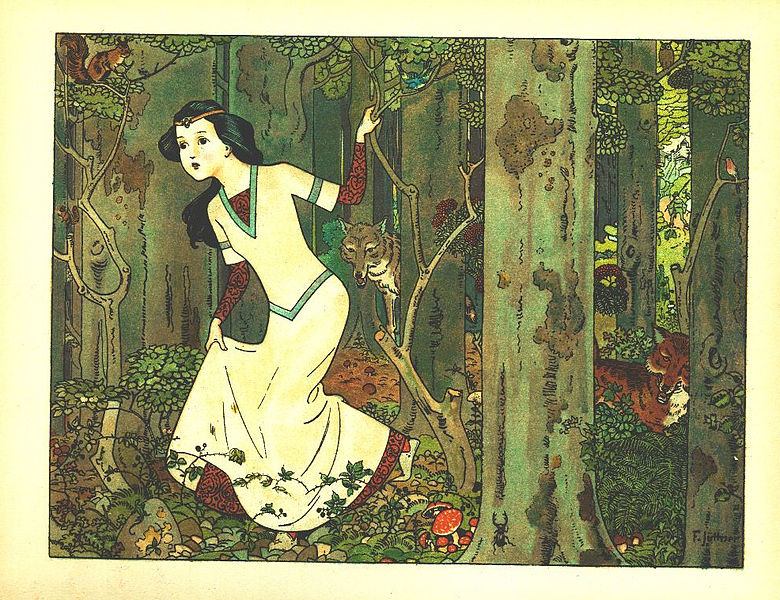

Out of all the treasures in the Book of Common Prayer, to me chief among them are the collects, the compendium of short and beautiful prayers, and chief among these is The Collect for Purity: My sister once bought a Dollar Store Snow White wig for my daughter. Three-year-old Ellie used to drag it behind her the way Linus clung to his blue blanket. She donned it at breakfast and slept in it at naptime. Day after day, wigged and rapt, she caressed the cheap dark locks with sticky toddler paws as Disney’s Snow White’s soprano pierced the thin walls of our apartment.

My sister once bought a Dollar Store Snow White wig for my daughter. Three-year-old Ellie used to drag it behind her the way Linus clung to his blue blanket. She donned it at breakfast and slept in it at naptime. Day after day, wigged and rapt, she caressed the cheap dark locks with sticky toddler paws as Disney’s Snow White’s soprano pierced the thin walls of our apartment.

Train us Lord to fling ourselves upon the impossible

Train us Lord to fling ourselves upon the impossible Though I am as dismayed as anyone by the current election year antics, I take comfort in remembering that bald-faced lunacy exercised in high places is nothing new. But I still have the sense that this election cycle is in a league of its own. Hopefully the bilious clouds of insanity swirling around us this fall will one day coagulate to something Americans can still recognize, once the whole thing is relegated to the history heap.

Though I am as dismayed as anyone by the current election year antics, I take comfort in remembering that bald-faced lunacy exercised in high places is nothing new. But I still have the sense that this election cycle is in a league of its own. Hopefully the bilious clouds of insanity swirling around us this fall will one day coagulate to something Americans can still recognize, once the whole thing is relegated to the history heap. A big bank just released a campaign with the following line, “A ballerina yesterday. An engineer today. Let’s get them ready for tomorrow.” When I saw it, a chuckle snuck out before I could muster up the will to be outraged. And I should be outraged. I should be offended and threaten to pull my patronage, at least, that’s what the dancers that make up a bulk of my Facebook newsfeed tell me. This advertisement is just one more national campaign that invalidates the important contribution artists make to society and discourages young people from careers in the arts, or whatever.

A big bank just released a campaign with the following line, “A ballerina yesterday. An engineer today. Let’s get them ready for tomorrow.” When I saw it, a chuckle snuck out before I could muster up the will to be outraged. And I should be outraged. I should be offended and threaten to pull my patronage, at least, that’s what the dancers that make up a bulk of my Facebook newsfeed tell me. This advertisement is just one more national campaign that invalidates the important contribution artists make to society and discourages young people from careers in the arts, or whatever.