Coming Undone

Tania Runyan

Just the other day I was paralyzed by these words:

“What would you do differently, you up on your beanstalk looking at scenes of people at all times in all places? When you climb down, would you dance any less to the music you love, knowing that music to be as provisional as a bug?. . .If you descend the long rope-ladders back to your people and time in the fabric, if you tell them what you have seen, and even if someone cares to listen, then what?”

The words are from Annie Dillard’s essay, “How to Live,” which first appeared in Image in 2001. I had been thumbing through the Bearing the Mystery anthology in the few minutes I had with my coffee before the kids came home. Now I heard the bus’s diesel engine rounding the corner and didn’t know what to do.

Writing that moves us, we say, makes us laugh or cry. It may even compel us to fight for justice, reach out to a stranger, say a prayer, or otherwise turn our lives around.

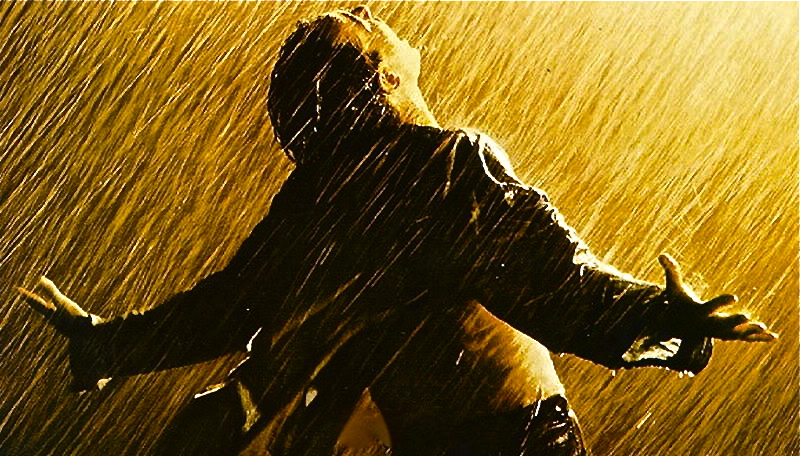

But this essay, this essay about my miniscule passions in “the infinite fabric of time that eternity shoots through,” rendered me helpless. I wasn’t so much overwhelmed with sadness or questions but numb, frozen-fingered in my ability to grasp anything. The fact that such a concept as eternity existed was enough, for the first time in my life, to make the floor tiles spin.

Some art does that—shifts the tectonic plates of our perceptions. It doesn’t inspire us but undoes us, haunts us until we view the image, listen to the piece, or read the essay again. I didn’t want to read it again. It made my stomach hurt, my breath shallow. But I went back to it later that day. Then again the next night. And the next. “Then what?” Dillard asks. Then what, then what, then what?

I still have no idea what to do.

But I know I would like to create something—even just one essay, poem, flowerbed or gingersnap—that leaves someone gaping like a caught fish.

Be still and know that you know nothing, the essay (Spirit? tiles?) seems to be whispering to me. Then work out of that.