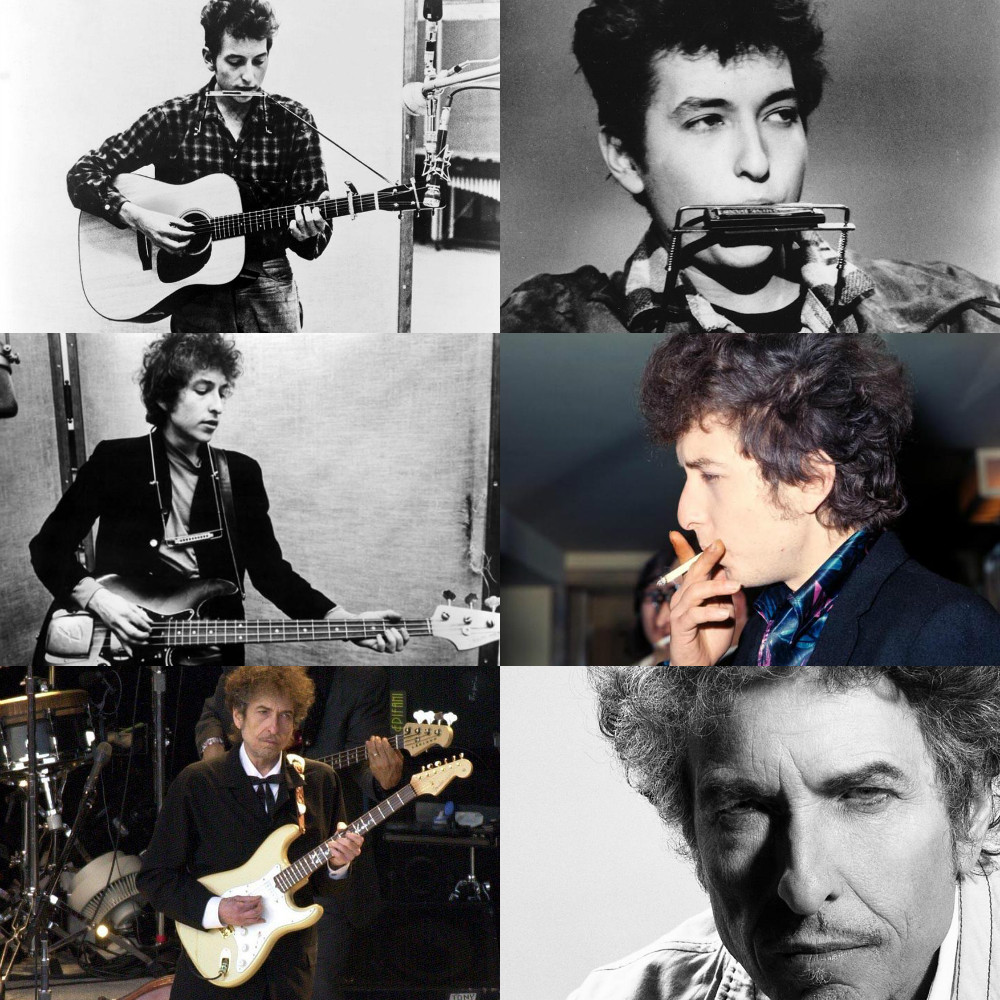

Dylan: The Times They Are A-Changin’

Jayne English

“Ah, but I was so much older then

I’m younger than that now."

—Bob Dylan

“Ah, but I was so much older then

I’m younger than that now."

—Bob Dylan

My brother began listening to Dylan when he was 17. That means I heard iconic lyrics like: “Well, they’ll stone you when you’re tryin’ to be so good/They’ll stone you just like they said they would” and “Once upon a time you dressed so fine/You threw the bums a dime in your prime, didn’t you?” drift through the house when I was 14. The guitar and harmonica, Dylan’s sometimes smooth, sometimes raspy voice wove their way through my mind and for years resided in the grooves of fond memory. I was immersed in “Blowin’ In the Wind,” “Tamborine Man,” “Lay Lady Lay,” “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” as they spun their familiar sounds from the turntable. Recently, feeling homesick for those songs, I listened to them again. I was surprised to find that the Dylan I knew opened to new and deeper levels.

It wasn’t just that I was older. During this same time I went back to listen to other music I inhabited as a teenager. Returning to Carole King and Carly Simon, for instance, felt just the same as it did in the past. But Dylan’s music now spoke in ways I never heard before. How is it that even his old songs can still be fresh today? Italian author Italo Calvino offers a simple point about what makes a literary classic: “A classic is a book which has never exhausted all it has to say to its readers.” Dylan’s work is new over time because it is deeply meaningful.

It continues to have something to say because Dylan has always been open to change, not holding himself to a constraint others wanted to impose. He got a lot of grief for it. He was constantly moving artistically, from writing topical songs like Woody Guthrie’s, to protest songs, to flashing image songs, and he famously switched from acoustic to electric guitar. He probably would never consider himself brilliant, but there is brilliance in his lyrics, music, and knowing not to hold onto categories, but to allow himself the freedom to chase change and ambiguity.

Dylan’s style could change because he is true to his inspirations. Among the many are Herman Melville, Lewis Carroll, James Joyce, Dylan Thomas, Arthur Rimbaud (“When I read [Rimbaud’s] words the bells went off.”), and Paul Verlaine.

After passing through the familiarity of nostalgia, I found in Dylan so much of the poetic soul of the Beats. When he was 18, someone gave Dylan a copy of Jack Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues. Dylan said the book blew his mind. When poet and friend Allen Ginsberg asked him why, Dylan told him, "It was the first poetry that spoke to me in my own language." Ginsberg continues to explain Kerouac’s influence on Dylan: “So those chains of flashing images you get in Dylan, like ‘the motorcycle black Madonna two-wheeled gypsy queen and her silver studded phantom lover,’ they're influenced by Kerouac's chains of flashing images and spontaneous writing.” In Dylan’s “Desolation Row” (1965) he blends these images and more: beauty parlor, circus, Bette Davis, Romeo, Hunchback of Notre Dame, iron vest, Noah’s rainbow, Einstein, a monk, pennywhistles, and mermaids. The Beatles were taken with Dylan’s lyricism and style. George Harrison says of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan album, "We just played it, just wore it out. The content of the song lyrics and just the attitude—it was incredibly original and wonderful."

As his audience attempted to confine him, Dylan resisted with all his creativity. In a 1966 Playboy interview, Dylan is asked, “Mistake or not, what made you decide to go the rock-'n'-roll route?” Dylan responds with an explanation that was more like an improvisational riff. He spun a tale of images that included a card game, crap game, pool hall, Mexican lady, Charles Atlas. It flows in a pastiche of people and plots and scenes. When he’s finished, the interviewer says, “And that's how you became a rock-'n'-roll singer?” Dylan replies, “No, that's how I got tuberculosis.” Dylan talks in imaginative circles and was often considered “contrary” by journalists because he knew that many people were not willing to listen to, and probably would not understand, his views on the artistic process.

In the same 1966 interview, Playboy reminds Dylan that he told someone he had done everything he ever wanted to do. “If that's true,” the interviewer asks, “what do you have to look forward to?” Dylan replied, “Salvation. Just plain salvation.” Dylan’s work, as it continues to speak, does offer a kind of salvation. As one author puts it, “it is in the nature of beauty to suggest the divine and the eternal.” I’m so glad I followed nostalgia’s pull to Dylan and found more of the place where beauty saves the world.

“Take a walk with a turtle. And behold the world in pause.”

—

“Take a walk with a turtle. And behold the world in pause.”

— I think of it like fingerprinting—fingerprinting for someone’s being-in-the-world.

I think of it like fingerprinting—fingerprinting for someone’s being-in-the-world. What they don't tell you is that getting older comes on you like a pie in the face: suddenly, unjustly, and funny to onlookers. And not funny to you. It comes like a slow-motion pratfall. It feels like a prank show genius has studied your increasing night-time eliminations and booby-trapped the route with a banana peel, a toy truck and a hoe in perfect succession. Aging comes blindly, symptom by symptom, each with its own joke.

What they don't tell you is that getting older comes on you like a pie in the face: suddenly, unjustly, and funny to onlookers. And not funny to you. It comes like a slow-motion pratfall. It feels like a prank show genius has studied your increasing night-time eliminations and booby-trapped the route with a banana peel, a toy truck and a hoe in perfect succession. Aging comes blindly, symptom by symptom, each with its own joke.

Kiss me, and you will see how important I am.

—

Kiss me, and you will see how important I am.

— On the second day of our impromptu beach vacation, Dennis decides to buy an electric planer at a local hardware store. “The oak panels need to be thinner, so they will resonate more once the harp is complete.”

On the second day of our impromptu beach vacation, Dennis decides to buy an electric planer at a local hardware store. “The oak panels need to be thinner, so they will resonate more once the harp is complete.” I was 27 years old when my daughter, my only child, Ellie, was born. It took years to conceive her, and then suddenly, on a pre-dawn Saturday morning, my water broke like the rainstorm that always arrives on days a meteorologist has confidently assured you, “Enjoy, folks. Today will be a sunny 70 degrees.” There were no signs Ellie would be a full three weeks early.

I was 27 years old when my daughter, my only child, Ellie, was born. It took years to conceive her, and then suddenly, on a pre-dawn Saturday morning, my water broke like the rainstorm that always arrives on days a meteorologist has confidently assured you, “Enjoy, folks. Today will be a sunny 70 degrees.” There were no signs Ellie would be a full three weeks early. “For the mouth speaks out of that which fills the heart”

—Matthew 12.34

“For the mouth speaks out of that which fills the heart”

—Matthew 12.34 “But Mole stood still a moment, held in thought. As one wakened suddenly from a beautiful dream, who struggles to recall it, but can recapture nothing but a dim sense of the beauty in it, the beauty! Till that, too, fades away in its turn, and the dreamer bitterly accepts the hard, cold waking and all its penalties.”

― Kenneth Grahame,

“But Mole stood still a moment, held in thought. As one wakened suddenly from a beautiful dream, who struggles to recall it, but can recapture nothing but a dim sense of the beauty in it, the beauty! Till that, too, fades away in its turn, and the dreamer bitterly accepts the hard, cold waking and all its penalties.”

― Kenneth Grahame,

I found the skin of a snake in my backyard last summer while I was crawling on my hands and knees pulling weeds. Sandwiched between stalks of crocosmia was an entire body case, white and transparent, stamped with tiny squares, like thin patterned tissue paper. Resting there whole, without the snake itself, I thought of the disciples finding Jesus’ grave clothes in the empty tomb. Where had he gone?

I found the skin of a snake in my backyard last summer while I was crawling on my hands and knees pulling weeds. Sandwiched between stalks of crocosmia was an entire body case, white and transparent, stamped with tiny squares, like thin patterned tissue paper. Resting there whole, without the snake itself, I thought of the disciples finding Jesus’ grave clothes in the empty tomb. Where had he gone? “Do you ever get used to such a place?’

She laughs then, a short bitter laugh I recognize and comprehend at once.

"Do you get used to life?" she says.

“Do you ever get used to such a place?’

She laughs then, a short bitter laugh I recognize and comprehend at once.

"Do you get used to life?" she says.

It’s hard writing about the salty Gulf Coast without the taste of fried biscuits in Mendenhall, Mississippi, or the hypnotic curves of rice paddies in southeast Arkansas, the lonely cotton gins and weathered Baptist churches that survive calamitous storms year after year. Before we can throw our bodies into the roiling sea, there’s a rite of passage we must traverse. It takes nine-and-a-half hours to drive from Little Rock to Orange Beach. Nine-and-a-half hours of poverty and the whims of commodity crop economics. It used to be cotton and rice. Now it’s GMO corn and soy. “You can’t even eat that corn,” my mom would say. A black cloud of starlings shoots past us. “I know, it all goes to the cows outside Denver,” I would reply. Dollar General replaced the mom-and-pop small town shops, and now even those soul-starved places are empty, only to be filled by storefront churches promising salvation by the highway. One sign reads Just Church. Fast food wrappers skitter along asphalt and half-smashed snakes. Upturned armadillos try to hold up the sky with their stubby legs. Meanwhile, kudzu swallows up longleaf pines and the lives that depend on them, and the forest turns into a tomb, encased by this foreign, medicinal vine only Agent Orange could knock out. The roadside greenbelt looks more like a freak show displaying storybook monsters frozen in time – their movements, their joys, their battles all swallowed up by this relentless vine. I don’t care how medicinal it is and what the rumors are for curing cancer. That vine is killing the forests.

It’s hard writing about the salty Gulf Coast without the taste of fried biscuits in Mendenhall, Mississippi, or the hypnotic curves of rice paddies in southeast Arkansas, the lonely cotton gins and weathered Baptist churches that survive calamitous storms year after year. Before we can throw our bodies into the roiling sea, there’s a rite of passage we must traverse. It takes nine-and-a-half hours to drive from Little Rock to Orange Beach. Nine-and-a-half hours of poverty and the whims of commodity crop economics. It used to be cotton and rice. Now it’s GMO corn and soy. “You can’t even eat that corn,” my mom would say. A black cloud of starlings shoots past us. “I know, it all goes to the cows outside Denver,” I would reply. Dollar General replaced the mom-and-pop small town shops, and now even those soul-starved places are empty, only to be filled by storefront churches promising salvation by the highway. One sign reads Just Church. Fast food wrappers skitter along asphalt and half-smashed snakes. Upturned armadillos try to hold up the sky with their stubby legs. Meanwhile, kudzu swallows up longleaf pines and the lives that depend on them, and the forest turns into a tomb, encased by this foreign, medicinal vine only Agent Orange could knock out. The roadside greenbelt looks more like a freak show displaying storybook monsters frozen in time – their movements, their joys, their battles all swallowed up by this relentless vine. I don’t care how medicinal it is and what the rumors are for curing cancer. That vine is killing the forests. Last night I dreamt that I got lost again. It’s a frequent dream for me: I can’t find my car or my way home. While that type of dream may have metaphorical meaning for some people, I think it is most likely pretty literal for me. When I was a kid, sometimes I had to ask my friends at sleepovers to remind me where their bathroom was because I couldn’t quite remember their house layout and I was scared of opening the wrong door. Before smart phones and GPSs, using public transit was a complete nightmare. In addition to having the tendency of getting lost, I am also pretty good at remaining unseen. It was not that uncommon for me to be the last one sitting on the bus patiently awaiting my destination when the driver would turn around, and, with a start say, “I had no idea there was still a passenger on here!” Sometimes, I had gotten on the right bus, but on the wrong side of the street and so ended up at the other side of the city.

Last night I dreamt that I got lost again. It’s a frequent dream for me: I can’t find my car or my way home. While that type of dream may have metaphorical meaning for some people, I think it is most likely pretty literal for me. When I was a kid, sometimes I had to ask my friends at sleepovers to remind me where their bathroom was because I couldn’t quite remember their house layout and I was scared of opening the wrong door. Before smart phones and GPSs, using public transit was a complete nightmare. In addition to having the tendency of getting lost, I am also pretty good at remaining unseen. It was not that uncommon for me to be the last one sitting on the bus patiently awaiting my destination when the driver would turn around, and, with a start say, “I had no idea there was still a passenger on here!” Sometimes, I had gotten on the right bus, but on the wrong side of the street and so ended up at the other side of the city. This fall, I plan to take my twelve-year old pheasant hunting for the first time, as my father took me. Last fall, when he was eleven, I took Micah out to shoot in a gravel pit outside of town, after which time I had one question:

This fall, I plan to take my twelve-year old pheasant hunting for the first time, as my father took me. Last fall, when he was eleven, I took Micah out to shoot in a gravel pit outside of town, after which time I had one question: