“Then the baker sat down at the table with them. He waited. He waited until they each took a roll from the platter and began to eat. 'It's good to eat something,’ he said, watching them. 'There's more. Eat up. Eat all you want. There's all the rolls in the world in here.’"

“Then the baker sat down at the table with them. He waited. He waited until they each took a roll from the platter and began to eat. 'It's good to eat something,’ he said, watching them. 'There's more. Eat up. Eat all you want. There's all the rolls in the world in here.’"

—from “A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver

When asked, I told the editors of this blog that my next post would be about “technology and human flourishing.”But I’m afraid I have nothing so grandiose to say. In fact, I had just one single image in my mind when I named that topic: people setting mobile devices on the dinner table. I know, what a super uptight and grumpy thing to discuss. Still…

When I consider my family and friends and eating together, I want to aim not for some idealized foreign film culinary-religious experience, but for a space where we can genuinely devote ourselves to one another. After all, it was nothing more or less than a supper where the bread and wine of the New Covenant were given for us.

In my experience, the presence of devices on the table, and the ubiquitous expectation that they will be employed at the first sign of wandering attention, can preclude the kind of intimacy that sustains me.

You know how you visit a business in person, then the business’s phone rings while you’re being helped? Often the salesperson makes you wait while he completes an entire transaction with the caller, and you think, “Glad I bothered to show up.”Watching people use devices when I’m at the table with them feels like that. Except worse, because ours is not a business relationship. We can do so much better than profit-driven corporate standards.

I’m not interested in building and defending traditional rhetorical arguments here. But I would like to present one more image to consider. (If you are looking for a compelling argument that touches on some similar themes, read Wendell Berry’s “Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer,”along with the follow-up letters that Harper’s readers wrote to him, and finally his response to those letters. These can be found in What Are People For?.

Back to my image: I’m picturing Ann and Howard Weiss, the parents of Scotty in Raymond Carver’s “A Small, Good Thing.” You’ll recall that Ann had ordered a birthday cake for her son, who then died after being hit by a car. The disgruntled baker, having no idea what had happened to the boy and only anxious not to lose money on the cake, calls the Weisses with irritation multiple times to tell them that they forgot to pick up their order. Finally, Ann and Howard go to the bakery to confront the man, whose calls seemed inexplicably cruel.

When the baker learns what has happened, he expresses deep remorse to the Howards. Then he senses, in an unspoken and profound moment, the rightness of eating and giving attention, which ultimately lead to the beginning of healing—not only for the Weisses but for the lonely baker, too. From that moment, nothing precludes them from entering an unusual, even frightening, depth of communion. (Ironically, it was a phone that led to misunderstanding and isolation. In person, they can break through.) The covenant has to do with presence—embodied love.

The final paragraphs of the story, for me, comprise one of the most spiritually poignant passages in 20th century American fiction:

"You probably need to eat something," the baker said. "I hope you'll eat some of my hot rolls. You have to eat and keep going. Eating is a small, good thing in a time like this," he said.

He served them warm cinnamon rolls just out of the oven, the icing still runny. He put butter on the table and knives to spread the butter. Then the baker sat down at the table with them. He waited. He waited until they each took a roll from the platter and began to eat. "It's good to eat something," he said, watching them. "There's more. Eat up. Eat all you want. There's all the rolls in the world in here."

They ate rolls and drank coffee. Ann was suddenly hungry, and the rolls were warm and sweet. She ate three of them, which pleased the baker. Then he began to talk. They listened carefully. Although they were tired and in anguish, they listened to what the baker had to say. They nodded when the baker began to speak of loneliness, and of the sense of doubt and limitation that had come to him in his middle years. He told them what it was like to be childless all these years. To repeat the days with the ovens endlessly full and endlessly empty. The party food, the celebrations he'd worked over. Icing knuckle-deep. The tiny wedding couples stuck into cakes. Hundreds of them, no, thousands by now. Birthdays. Just imagine all those candles burning. He had a necessary trade. He was a baker. He was glad he wasn't a florist. It was better to be feeding people. This was a better smell anytime than flowers.

"Smell this," the baker said, breaking open a dark loaf. "It's a heavy bread, but rich." They smelled it, then he had them taste it. It had the taste of molasses and coarse grains. They listened to him. They ate what they could. They swallowed the dark bread. It was like daylight under the fluorescent trays of light. They talked on into the early morning, the high, pale cast of light in the windows, and they did not think of leaving.

I would suggest that each one of us is perpetually Ann and Howard. Each of us is the baker. When we break bread together, we bring our hurts and fears, loneliness, the very stories of our lives, to the table. Let us partake while giving one another the attention our communion needs in order for each of us to flourish.

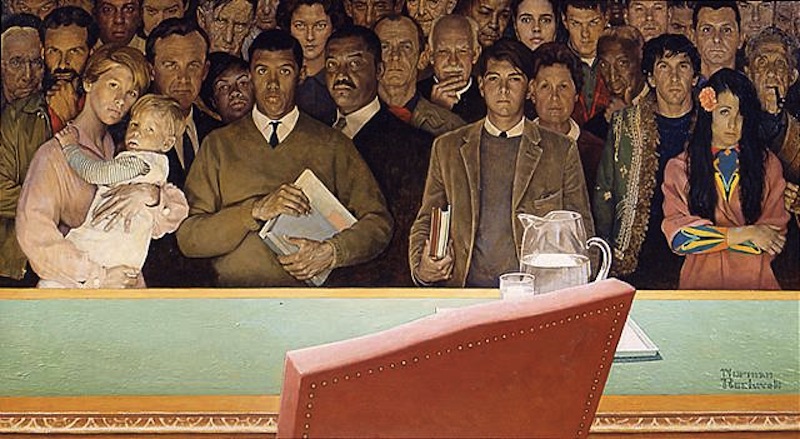

(Painting by Jan Steen)