The Russian Soul Rises

Vic Sizemore

Boris Pasternak had worked on it for half of his life. When Boris Pasternak handed a secret copy of his sweeping epic Doctor Zhivago to an agent for an Italian publisher, he said, “You are invited to my execution.” He was not being melodramatic. The novel had been rejected by the authorities in Soviet Russia — writers who sneaked their work out for foreign publication had a habit of waking up dead — and he was looking elsewhere. When the novel was published in Italian in 1957, and in English in 1958, some 1,500 writers had been executed or died in concentration camps since the 1917 revolution.

Boris Pasternak had worked on it for half of his life. When Boris Pasternak handed a secret copy of his sweeping epic Doctor Zhivago to an agent for an Italian publisher, he said, “You are invited to my execution.” He was not being melodramatic. The novel had been rejected by the authorities in Soviet Russia — writers who sneaked their work out for foreign publication had a habit of waking up dead — and he was looking elsewhere. When the novel was published in Italian in 1957, and in English in 1958, some 1,500 writers had been executed or died in concentration camps since the 1917 revolution.

The nature of the Soviet Union’s persecution of artists and intellectuals is stuff of legend, as is Pasternak’s role, but what was it about the novel that they found so threatening? A fictional character: Zhivago himself.

Yuri Zhivago is born, as was Pasternak, in 1890. When his parents die, he is sent to live with relatives in Moscow. Concerned with social justice and the plight of the poor, Zhivago, like Pasternak, initially supports the revolution, but quickly becomes disillusioned when it becomes clear that the Bolshevik’s rule is based on blood and brutality. His life is circumscribed by the events of the revolution, but he continues to attempt to live meaningfully. Though he is a flawed man, he manages to do some good and love deeply, which under his circumstances could almost be considered success.

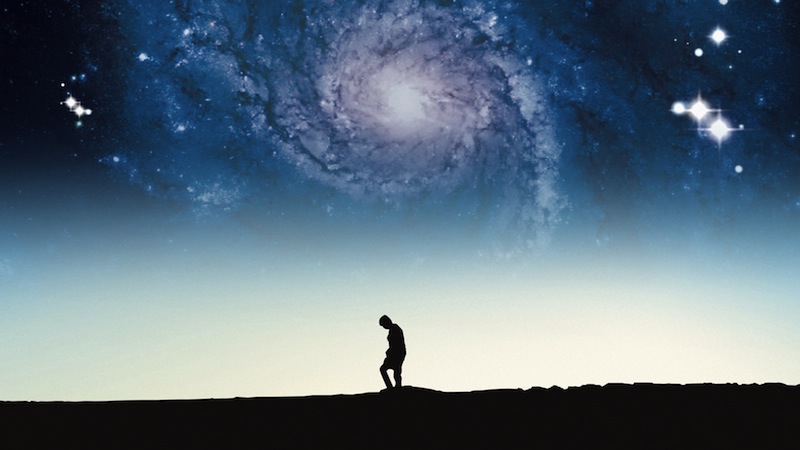

Speaking of his own weak heart to two friends, Zhivago tells them that cardiac hemorrhages are becoming more frequent in Russia. He says, “It’s the disease of our time. I think its causes are of a moral order.” He continues, “Our soul takes up room in space and sits inside us like the teeth in our mouth.” He says, “It cannot be endlessly violated with impunity.” He speaks the truth that the Soviet authorities seek to suppress, to deny.

Dr Zhivago’s failure to be heard in the novel is simply, according to a Masterpiece Theater essay, “a sign that he was destined to become an artistic witness to the tragedy of his age.” He was also the Russian everyperson.

“You can make the Russian soul suffer,” Doctor Zhivago shouted to the Soviet authorities, “but it is indomitable — you cannot keep it down.”

Indeed, the threat Zhivago presents to the Soviets was clear from the first lines of the novel. As Frances Stoner Saunders explains, “‘Zhivago’, in the pre-revolutionary genitive case, means ‘the living one’. On the novel’s first page a hearse is being followed to the grave. ‘Whom are you burying?’ the mourners are asked. ‘Zhivago’ is the reply, punningly suggesting ‘him who is living’.”