On Taking Note

Callie Feyen

One summer, my family spent an afternoon riding bikes on Mackinac Island. During the eight-mile ride, I noticed several piles of rocks ranging from just a few stones to almost three feet high. I learned from the brochure I carried in my bike basket that these are called “cairns,” and they’re used to mark trails by hikers and bikers; mostly at points where the trail isn’t obvious or there’s a sharp decline. However, the cairns on Mackinac Island weren’t on trails. In fact, they were scattered over the shore. The Mackinac Cairns, I learned, served “as a memorial for having been somewhere or as a simple art form.” I laughed at first, and thought, “simple indeed” as I watched my six- and four-year-old daughters pile rocks on a break from riding bikes. I wondered about the memorial part of this practice as well. What was seen or heard, what was the weather like, and what else happened while rocks were being piled up? I was annoyed that I didn’t know the story, and instead, had to look at the lake, the sand—nature—and wonder what in the world would make someone get off her bike and stack four or five rocks in a pile.

One summer, my family spent an afternoon riding bikes on Mackinac Island. During the eight-mile ride, I noticed several piles of rocks ranging from just a few stones to almost three feet high. I learned from the brochure I carried in my bike basket that these are called “cairns,” and they’re used to mark trails by hikers and bikers; mostly at points where the trail isn’t obvious or there’s a sharp decline. However, the cairns on Mackinac Island weren’t on trails. In fact, they were scattered over the shore. The Mackinac Cairns, I learned, served “as a memorial for having been somewhere or as a simple art form.” I laughed at first, and thought, “simple indeed” as I watched my six- and four-year-old daughters pile rocks on a break from riding bikes. I wondered about the memorial part of this practice as well. What was seen or heard, what was the weather like, and what else happened while rocks were being piled up? I was annoyed that I didn’t know the story, and instead, had to look at the lake, the sand—nature—and wonder what in the world would make someone get off her bike and stack four or five rocks in a pile.

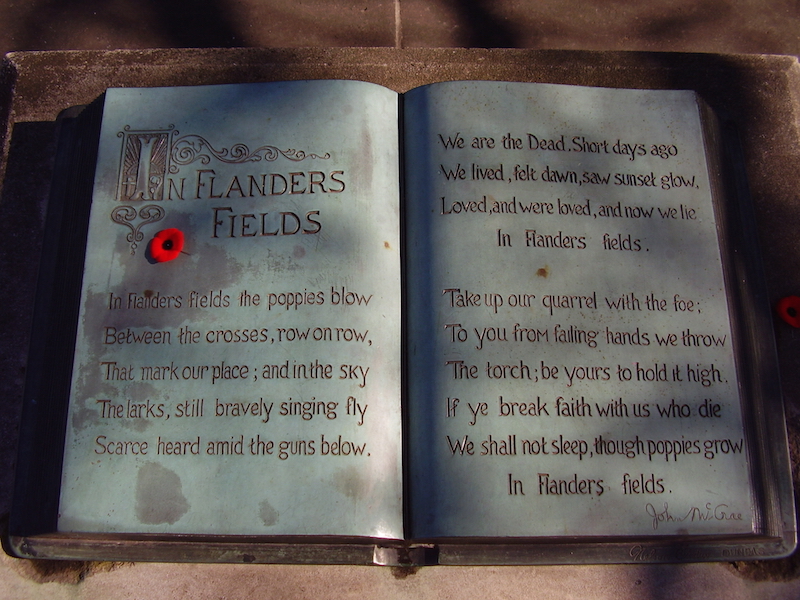

The idea of taking note of something in one’s day with little to no reflection is explored in an essay titled, “Rambling Round Evelyn,” in the book The Common Reader by Virginia Woolf. Throughout the essay, Woolf examines the diary, which could also be thought of as a memorial for having been somewhere, as well as a simple art form. Woolf uses the diary of John Evelyn to show that while simply taking note might seem tedious and perhaps unnecessary, it also can spark wonder and imagination of those who are left behind to observe it.

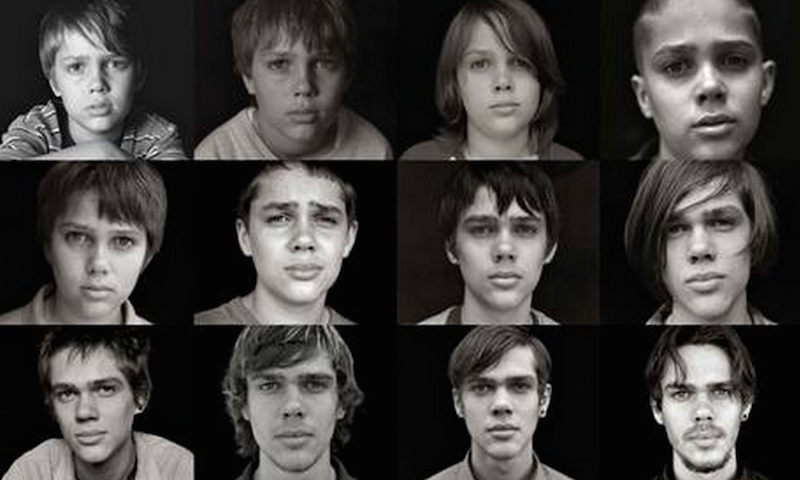

John Evelyn was meticulous about recording the events of his days, but it was the event he was focused on, not his thoughts and feelings about it. Woolf doesn’t consider this writing. In fact, in her own diary, she writes, “this diary writing does not count as writing, since I have just re-read my year’s diary and am struck by the rapid haphazard gallop at which it swings along, sometimes indeed jerking almost intolerably over the cobbles.” Woolf thought that the real task of a writer is not just writing down the facts, but to help the reader see something beyond those facts, and Evelyn does not do this in his diary. He records, and he moves on. Almost all of the work is left to the reader to decide whether what he saw is worth noticing too.

However, this is not to say what Evelyn did didn’t have merit or that keeping a diary is a waste of time. While Woolf might’ve not thought it was writing, she wrote about her own diary keeping: “The advantage of the method is that it sweeps up accidentally several stray matters which I should exclude if I hesitated, but which are diamonds of the dustheap.” Further, Woolf explains that the reason Evelyn kept a diary was because it was, “as if the look of things assailed him.” What Evelyn saw attacked him and the only thing he could do to manage this fierce sensitivity to the world was write them down.

“Evelyn was no genius. His writing is opaque rather than transparent; we see no depth through it, nor any secret movement of mind or heart,” Woolf wrote. But more than 300 years later, his diaries still exist and if we are to read them it will be up to us to see “these scattered fragments—like relics of beauty in a world that has grown indescribably drab.” I think it is this active participation on the part of the reader that makes diary writing an art form.

If I wanted, I could add stones to the existing piles scattered around the island; a symbol to show I noticed, I saw something beautiful or startling, too. But that is all. I could not say what it was or why it gave me pause. All I could do is pick up another rock and place it on the pile to mark my spot, hoping it didn’t crumble.