From Ache to Amen

Adele Gallogly

A few Decembers ago, I saw Handel’s acclaimed Messiah oratorio in concert for the first time. From our side balcony seats at the Roy Thompson Hall in Toronto, my friends and I had an overhead view of the choir as well as the orchestra stage. We could only see the backs of the interchanging soloists, which worried me a little. Would the experience be lessened by this limited view? A few minutes into the show, however, I realized that we could see something that the coveted, pricier center section below could not: the face of the conductor.

A few Decembers ago, I saw Handel’s acclaimed Messiah oratorio in concert for the first time. From our side balcony seats at the Roy Thompson Hall in Toronto, my friends and I had an overhead view of the choir as well as the orchestra stage. We could only see the backs of the interchanging soloists, which worried me a little. Would the experience be lessened by this limited view? A few minutes into the show, however, I realized that we could see something that the coveted, pricier center section below could not: the face of the conductor.

This conductor was, in a word, animated. He waved his arms and wielded his baton with a wizard-like flourish to guide the skilled group of musicians. His face is what caught me, though. His features echoed the emotional tone of each movement—tight and serious in moments of lament, open and bright in moments of delight. He smiled during that famous chorus.

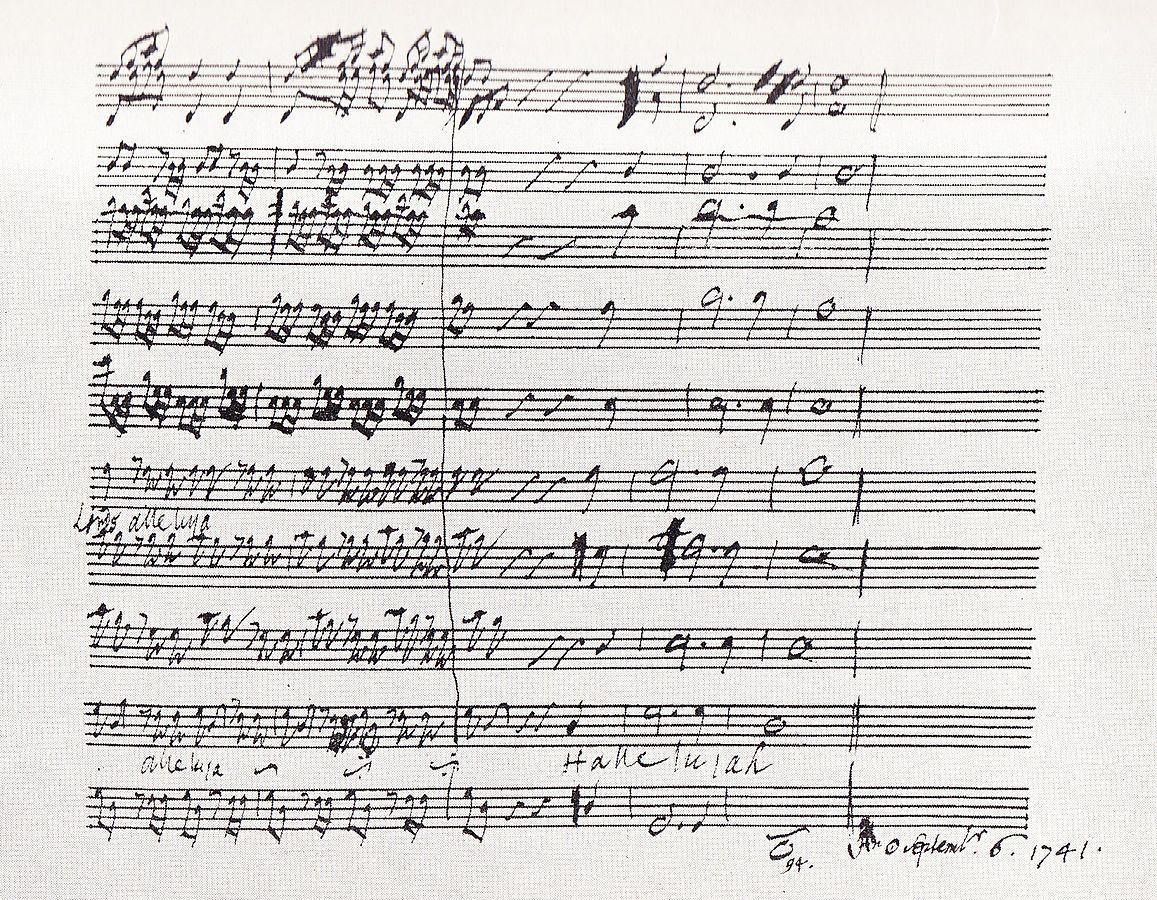

Anecdote has it that Handel’s own face was wet with tears after he wrote the Hallelujah chorus. His assistant came upon him crying at his desk and asked him: “What’s wrong?” To which Handel replied. “I thought I saw the face of God.”

After such a splendorous vision and satisfying creation, it is a wonder that Handel went on to write another act at all. Yet he did.

In Philip Yancey’s reflection on Messiah’s “bright and glistening theology," he recalls the various theories behind King George II standing during the Hallelujah Chorus at the oratorio’s London premiere. Some believe did so because he was emotionally moved. As Yancey points out, however, there are also those who suggest that the king in fact rose to his feet because he mistakenly believed the show was over. Apparently novices in the audience have been known to make the same error today.

“Who can blame them?” says Yancey. “After two hours of performance, the music seems to culminate in the rousing chorus. What more is needed?”

Handel had an entire act of “more” to add. A heavy act. This brilliant composer, this creative man of God, recognized that as heavenly as his chorus sounded, it was still a chorus of earth--a place where so much is wrong and so much is needed.

In what Yancey heralds as “a brilliant stroke,” the final act begins with words from a stricken Job. It seems a steep fall from ebullient Hallelujah to a story of such tragedy. But there is a brave hope in Job's persistence of belief. The Christ that Handel then dwells on is the Christ of Revelation 4-5—the slaughtered Lamb, the humble sufferer whose victory comes through surrender.

“The great God who became a baby, who became a lamb, who became a sacrifice—this God, who bore our stripes and died our death, this one alone is worthy,” says Yancey. “That is where Handel leaves us, with the chorus "Worthy Is the Lamb," followed by exultant amens.”

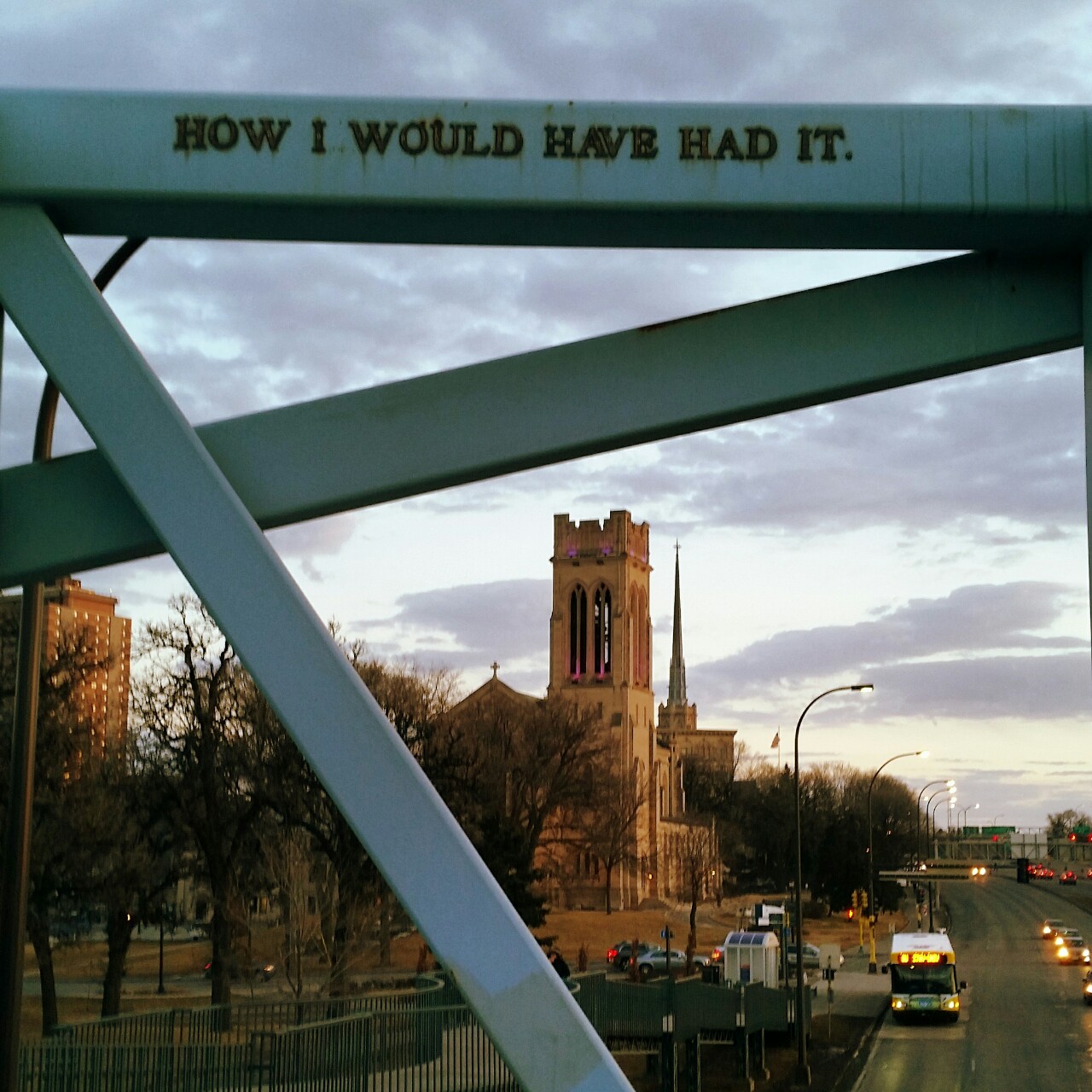

Messiah’s expansive view is shown in its refusal to skip over wounds and tears to get to exultations. There is anxiety. There is uncertainty. There is blood. Handel acknowledges that here, in this sin-wrung world, our cries to the Lamb do not always sound like Hallelujahs. Sometimes they sound like weeping, or groaning. Like…ache.

As Handel’s “bright and glistening theology” swirled around me live that first time, my enjoyment of the piece was rimmed with specific aches. Ache for Opa (grandfather), who passed away a few years earlier and used to see Messiah in concert with my Oma, year after year. Ache for a coworker who was, at that very moment, stricken with the pain, exhaustion, and delirium of leukemia. In years prior I heard him loudly singing along to Messiah in his office. That was to be his last Christmas; a month later he would pass away. I ached, too, with awareness of the painful arcs in so many people's lives—persecution, loneliness, war, depression, disaster. The list goes on. As does the ache in our world.

Handel’s Messiah is as honest in its agony as it is in its joy. Its chords anticipate a world restored without diminishing the woundedness of living in the not yet. This is its gift: a true vision of Emmanuel, a Lord who is not just visible to us, his children, but present with us. He rejoices with us and carries our sorrows. May we look closely, sing boldly, and listen well as we seek His face.

Blessing, and honour, glory and power, be unto Him that sitteth upon the throne, and unto the Lamb for ever and ever. Amen.