I Feel the Air of Another Planet: What’s to Love About Picasso, Silliman, and Schoenberg?

Jayne English

“Does man love Art? Man visits Art, but squirms. Art hurts. Art urges voyages— and it is easier to stay at home, the nice beer ready.” - Gwendolyn Brooks

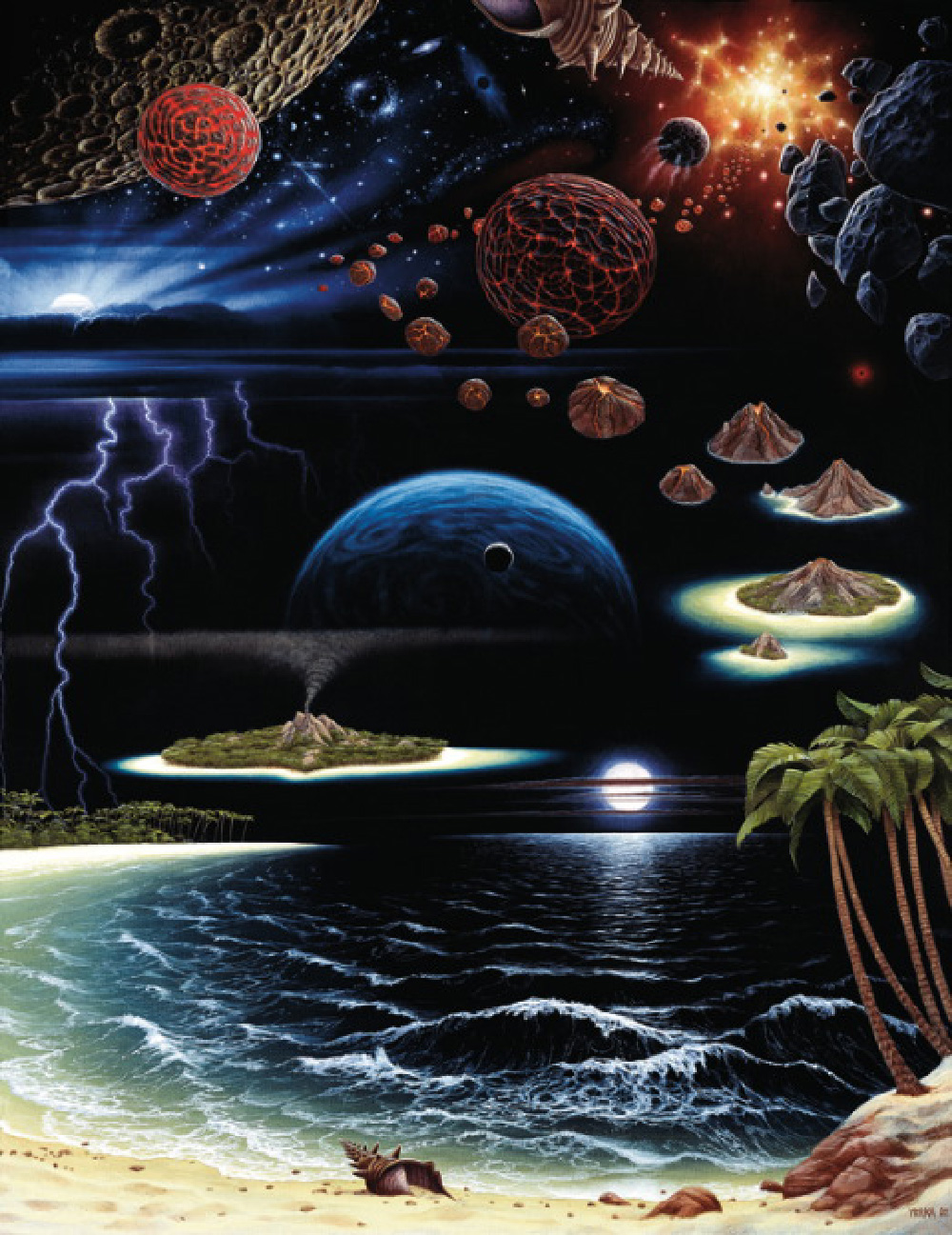

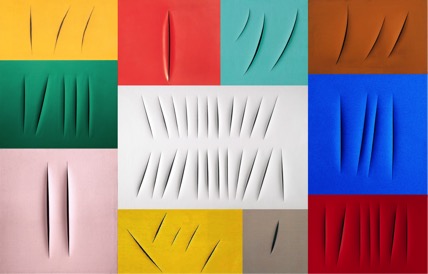

I recently attended a show of Dali and Picasso works that were exhibited side by side. The gallery was a forest of people listening through headsets to a self-guided tour. On two occasions I came upon someone standing back from a painting, head cocked, telling a companion “I can’t see it.” One even approached a painting and, being careful not to touch the canvas, outlined a particular area in explanation for a friend who shook her head in response. Those two—Picasso and Dali—always trying to shake up our ideas of what is art (and maybe, reality). In Picasso’s Woman in an Armchair, I couldn’t see the woman either. But somewhere along the line, I lost the propensity to search out recognizable shapes in paintings (which oddly enough, coincided with my ability to see shapes in clouds). The less I try to find the woman, the more I find other things. In the gallery, I approached this perplexing painting and happily discovered a nice blend of colors, texture that begged to be touched, and a thought provoking juxtaposition of shapes. I was surprised to notice a block of leopard print which I took to be a cuff of the invisible lady’s dress. Though it could just as easily be a portion of a rug because by leaving the meaning ambiguous, Picasso welcomes the viewer to participate in its interpretation.

Inviting the audience to weigh in on the work’s meaning is also a goal of Language poets like Ron Silliman. Silliman’s poem “BART” is one, ten-page sentence. You have to let go of your dependence on grammatical elements because the work is disjointed and lacks the usual clauses and punctuation. But I really like how this openness allows me to make my own associations. As Silliman spends a Labor Day traveling and writing on a Bay Area Rapid Transport train, his non-linear approach gives my imagination freedom to explore. Here’s how BART begins: “Begin going down, Embarcadero, into the ground, earth’s surface, escalators down, a world of tile, fluorescent lights, is this the right ticket, Labor Day, day free of labor, trains, a man is asking is there anything to see, Glen Park, Daly City, I’m going south which in my head means down but I’m going forward,…” (Read the rest of it here.) Silliman leaves meaning open for his readers to discover. As Picasso used juxtaposition of shapes, Language poets un-anchor clauses and phrases at odd angles to stir our thoughts beyond a sentence or paragraph’s usual track.

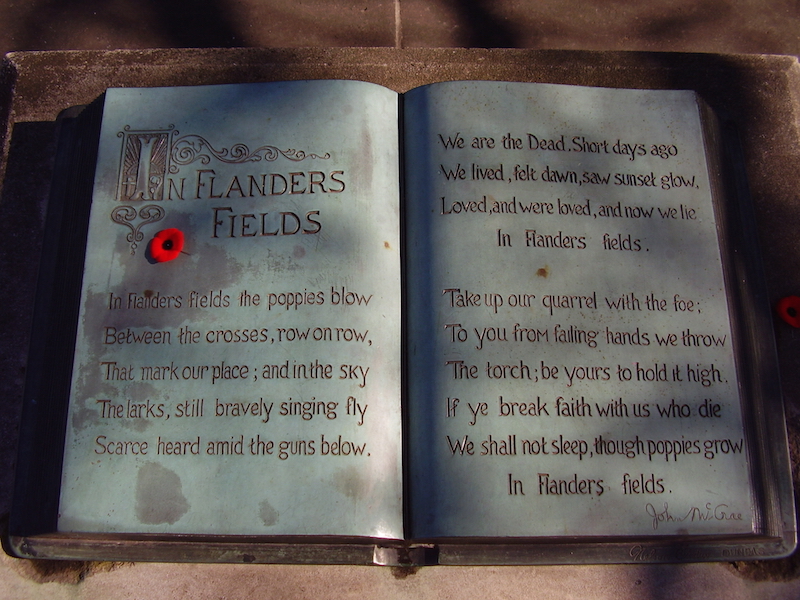

The cascading walls of shape and meaning, and the beckoning of other worlds are also what draw me to atonal music. Schoenberg does with notes what Picasso does with shape and Silliman does with words. In 1908, when Schoenberg performed his Second String Quartet (traditionally made up of a viola, cello, and two violins), the audience was surprised when he introduced a soprano in the third movement. Actually, they hissed and shouted for her to stop. The lyrics are from the poetry of Stefan George, itself full of feeling but complicated by the soprano’s scripted part in the disharmony. As the piece became progressively atonal, the audience grew progressively hostile. Schoenberg opens the third movement with a dusting of notes reminiscent of a sci-fi spaceship, and these words from George, “I feel the air of another planet.” Schoenberg accurately, if unknowingly, predicted how his innovations would alienate and rub his audience “raw,” an image Brooks uses later in her poem.

As these artists set us adrift on voyages, their work chafes and intrigues. Can this be one way art imitates life? Maybe by leaving “the nice beer ready,” we are able to encounter new spheres. A further power of these kaleidoscopic works is that they add new dimension to the more linear and harmonious expressions when we do return “home.” Silliman says this about disjuncture in his poetry: “I’m more or less working on methods that allow people to experience the world as freshly as possible as constantly as possible.” Surely, we need answers in life. But maybe art is more about the questions. Bon voyage?

(For further exploration, find Schoenberg’s Second String Quartet, Opus 10 here. Under “Show More,” you’ll find the four time marks for each of the four movements. Follow Stefan George’s poem in the last two movements in German and English here on page 6. Read the rest of Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem “The Chicago Picasso” here.)