My 8th grade classroom smells like mint gum, and body odor. The gum is not allowed. I am to tell the kids to get rid of it, and then report it into a shared record system that’s stored on the computer. After a certain amount of gum busts, I think the student gets a detention or something along those lines.

My 8th grade classroom smells like mint gum, and body odor. The gum is not allowed. I am to tell the kids to get rid of it, and then report it into a shared record system that’s stored on the computer. After a certain amount of gum busts, I think the student gets a detention or something along those lines.

There is no rule against body odor. Body odor is allowed in my classroom, and by the end of the day the smell is knock-you-over palpable. So I say nothing about the gum because each shift in a chair, each reach for a book, stapler, or clipboard, each step towards the “complete work box” brings with it a stench followed by a cool minty breeze.

“Mrs. Feyen,” one boy walks up to me while I’m standing at a counter in the back of the room sorting through papers.

“Yes?” I ask and pivot towards him.

“I don’t understand this assignment. You want me to write about something beautiful, but it has to be bad in some way?”

As he asks, I see bright green gum stuck to his bottom teeth. When I was a kid, I was so careful to keep the gum at the roof of my mouth. I could even fold a Fruit Roll-Up so it perfectly fit inconspicuously in my mouth and I could enjoy it from noon until three. My teachers never knew a thing. I am sure of it.

“I want you to write about a time when you saw beauty in a situation where beauty didn’t seem to belong.” He looks at me like I’ve answered in Japanese. He shifts, than scratches his forehead. If we are going to continue this conversation, I need him to start chewing that gum to balance out the smell.

“Like Mayella’s red flowers in slop jars in her front yard,” I remind him. We’ve just finished studying that scene in To Kill a Mockingbird and I want my students to do what Harper Lee did; write about beauty that baffles.

“Can you think of a time when you were really scared, or really angry, or really sad, and you noticed something funny, or pretty, or even interesting?”

He isn’t staring at me blankly now, and I think something is starting to take shape, but he wants more.

“The thing you noticed didn’t fix the situation,” I say. “I mean, it doesn’t make everything all better, but you noticed it. That’s what I want you to write about.”

He’s chomping his gum now and nodding vigorously. “OK,” he says, “I got something.”

I should tell him to spit his gum out now, but I’m afraid it’ll break the spell, so I choose not to, and he pivots, leaving me in a wake of B.O. and mint gum, and the unease of letting him off the hook.

****

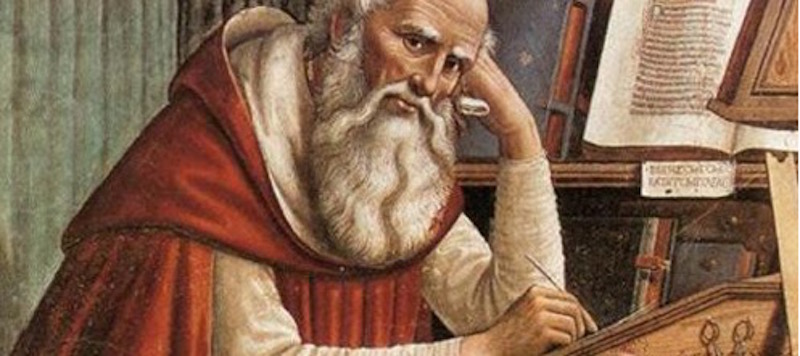

In her book, Wearing God, Lauren Winner writes about finding God in smell. She tells of a homeless man who sued a public library because he was banned from it due to his smell. Other people couldn’t focus because of this man’s body odor. At first, the court sided with him, but in a second case, the court sided with the library.

Winner contemplates this incident along with similar situations she’s experienced in her city, and she decides that this sort of reflective thinking is a form of prayer. “Prayer in which you replay scenes from your day, scenes from your year, and try to see God in them, or try to see them with God standing alongside you, looking too…What do I see when I try to look with God?”

****

The kid writes about a park in his neighborhood where he goes quite a bit to play sports with friends, but he also shows up alone, on days when he wants to pray. He climbs trees and prays. He has a lot on his mind, he writes, a lot to figure out. But he likes those trees with their sturdy trunks and thick leaves.

“Jesus,” Winner writes, “was a sometimes homeless man whose body was not always perfumed by women bearing nard. He surely sometimes stank.”

I smell thirty-one images of God in my classroom. Sometimes they reek. Sometimes they blatantly break the rules. Always they bring with them beauty that confuses, overwhelms, doesn’t fit in. I believe it is my job to help them notice and name this ridiculous, life-saving beauty.

****

It is May. The last instructional day of class and my students have to write two exit essays to show where they are as writers. One essay is narrative: write about something memorable. The other is expository: explain something you know well. The kid who goes to the park to pray raises his hand, and I walk over. He switches his gum to the other side of his mouth. I guess he thinks it’s not as obvious there.

“Mrs. Feyen,” he says. “For my expository essay I want to write about baffling beauty.” That’s what I called their writing assignment back in October. “Do you think the high school teachers will understand what I’m talking about?”

I stand and take a quick survey of these kids I’ve spent nine months with. The kids I have to say goodbye to, who in less than four years will be adults. They’ll be able to chew gum whenever and wherever they please, and they’ll have this B.O. thing figured out by then. But right now, I get to work with the image I’ve been given, and that’s just fine with me.

I lean towards my student and I smell all of it: dry erase markers, the air-conditioning, carpet, mud, and yes, mint gum and body odor.

“I think you better explain what you think baffling beauty means,” I tell him.

In 1999, Mark Wallinger created a statue of Christ wearing a crown of thorns. He named the statue Ecce Homo ("Behold the Man"). It was not chipped out of stone or carved out of wood, but was instead made out of a plaster-and-marble-powder cast of a human body. The piece was a temporary installation that stood on the empty "fourth plinth" in Trafalgar Square in central London. Being made from a human cast, it was literally life-sized and dwarfed by the imposing surroundings of the square.

In 1999, Mark Wallinger created a statue of Christ wearing a crown of thorns. He named the statue Ecce Homo ("Behold the Man"). It was not chipped out of stone or carved out of wood, but was instead made out of a plaster-and-marble-powder cast of a human body. The piece was a temporary installation that stood on the empty "fourth plinth" in Trafalgar Square in central London. Being made from a human cast, it was literally life-sized and dwarfed by the imposing surroundings of the square.