The Somedays Between Now and Then

Chrysta Brown

When I committed to writing about getting older, I thought the words would come easily. After all, aging is something that has been happening to me for my entire life. I was born. I turned 10, 16, 18, 21, and 25, and someday I will be 40, then 60, then maybe 85. But before that, I will turn 27.

When I committed to writing about getting older, I thought the words would come easily. After all, aging is something that has been happening to me for my entire life. I was born. I turned 10, 16, 18, 21, and 25, and someday I will be 40, then 60, then maybe 85. But before that, I will turn 27.

When I was 11, I had a very clear picture of what I thought my life would be in my twenties. I remember thinking I would be married and living in New York City. I expected that I would drive to my job as a ballet dancer in a black SUV with tinted windows. I thought that I regularly would take in deep breaths of clean air, revel in unobscured views of blue skies, and shove my manicured fingers into the pockets of one of my many puffy vests. These seemed like perfectly realistic goals.

Now that I am actually in my twenties, here are the things I can check off: puffy vests (without the manicure). There are some days—these are the days when I choose takeout over a Pinterest recipe or store bought cookies over something baked from scratch with love, or the days when I post a picture of coffee instead of a selfie of me and my other half—I feel like a failure as an adult. I feel like, in the words of Nora Ephron in “I Remember Nothing,” “On some level, my life has been wasted on me.”

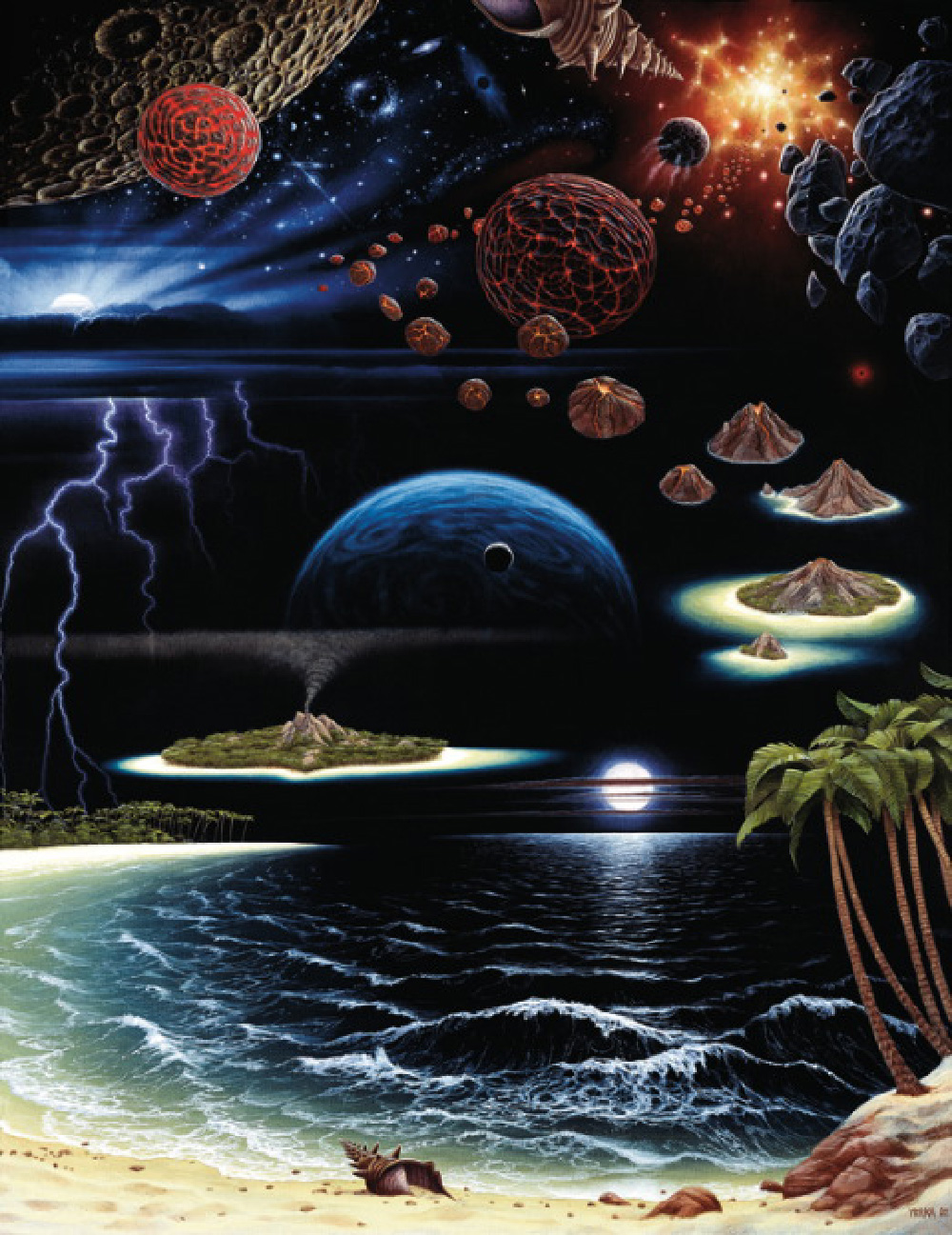

I have to take a break from musing and confess that, much like my life, this piece is not going as I planned. I thought that at about this point this collection of feelings would culminate into some really hopeful and clever words of wisdom. I was thinking something like, "Here I am, soon to be 27, floating in the ocean of time as my Someday (this is a When Harry Met Sally reference) approaches. I cannot gauge the upcoming wave, but I know how to swim, and I am ready for whatever the future brings.” Every time I read it, my voice changes to something that sounds like the narrator of a My Little Pony audiobook, the one that comes with a booklet of scratch-and-sniff stickers. It is irritating and kind of dumb.

I am struggling to tie these pieces together into a box that looks like it came from Pottery Barn. I am searching for story development, the clear plot structure, the moment where the ending becomes clear. I do recognize that I am searching for this ending in the middle of my story, but it is easy to feel that time is moving faster than my ability to acclimate to being grown up. It turns out that aging, much like writing, is hard. At some point in my life, probably when I thought that writing would be fun, I became obsessed with deadlines. While you can impose deadlines on creative pieces about life, you cannot, it seems, always apply them to life itself.

That's pretty tidy. I could end it there, but the question that I'm trying to answer is what exactly I'm supposed to do with that information. At this age, I should know things, but I don't think I do. I haven’t gotten to the point where I feel like I know what I’m doing. That is probably more frustrating than life's need to ruin my plans.

In “The O Word,” an essay Ephron wrote at 69, she says she spent a bit of time thinking about the secret to getting older. “I would like to have come up with something profound, but I haven’t. I just try to figure out what I really want to do every day…I aim low. My idea of a perfect day is a frozen custard at Shake Shack and a walk in the park (followed by a Lactaid).”

When it comes to conjuring up a profound ending to my own musings, I too come up short. At 26, there's no way to talk about aging without sounding like those newlyweds that love to give out relationships advice. While I may be old to my five-year-old students, and old enough to switch to an anti-aging moisturizer, according to the expected lifespan in the US, this is only a quarter-life crisis and not one in the middle. So here is what I am going to do. I will call the Thai restaurant down the street. When the owner asks for my name, I will tell him, and he will say “Ah, yes, Chrysta Spicy Gluten-free,” as if that is what is printed on my ID. I will find it endearing and also a little embarrassing, but I will get over it long enough to find satisfaction in eating the food straight from the container and not having dishes to wash afterwards. Then I will go to sleep, and when I wake up, I will be one day older.