An Unexpected Journey

Callie Feyen

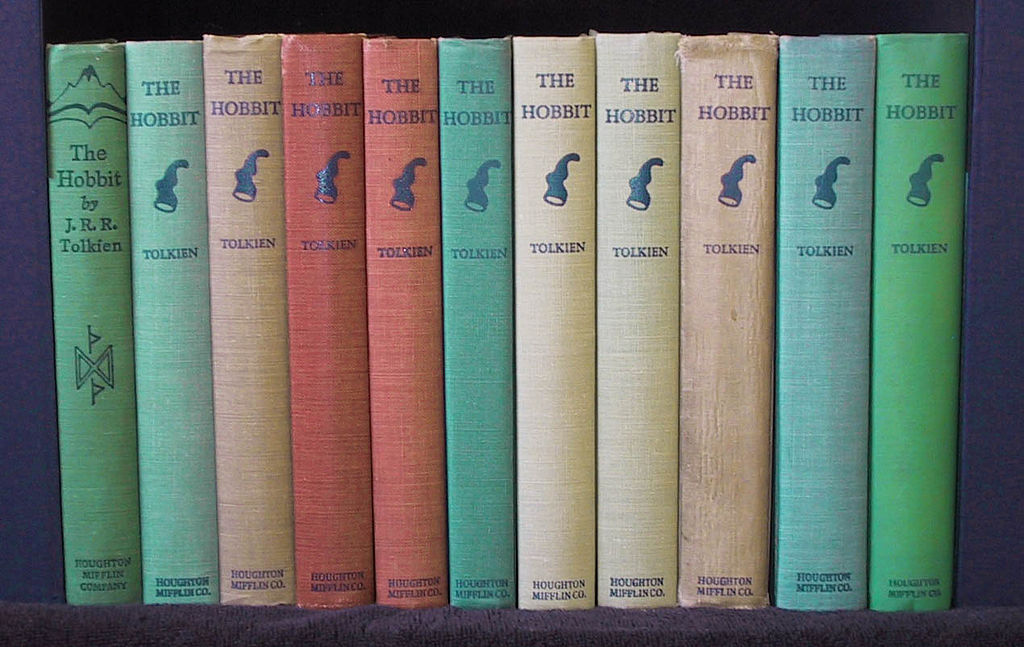

I am reading The Hobbit for the first time. I am 40 now, and I am reading it because I have to teach it to 7th graders.

I am reading The Hobbit for the first time. I am 40 now, and I am reading it because I have to teach it to 7th graders.

I believe it’s important I tell you my age and my motive for reading J.R.R. Tolkien because it’s embarrassing. I should’ve discovered the Misty Mountains, I should’ve gasped when Bilbo slips “a golden ring, a precious ring” on his finger, I should’ve considered how to blow smoke rings and having second breakfasts years ago when summers meant riding my bike and chasing fireflies until my mom called, “Callie, come home!”

I was not a reader growing up, and I have so much to catch up on: Tolkien and Eliot, and Shakespeare, and I haven’t even read all of Judy Blume’s books.

Reading is hard for me. I have to read The Hobbit with reading guides and synopses of each chapter. One night my husband came home from work to find me sobbing, my head in my hands, moaning, “I don’t get this. I’ll never understand it. I hate those damn elves!”

That evening, he made his from scratch taquitos and strong margaritas (he only knows how to make them strong) and he found Peter Jackson’s film, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey online.

“Oh,” I said when the red paper kite dragon flew into view. “That’s foreshadowing. The paper dragon’s there because it’s the dragon that stole all that gold.” I took a sip of my drink then said, “I think I remember that dragon can’t do anything with the gold. Is that right?” I looked at Jesse for a moment, then back at the TV. “I mean, I think the dragon can’t enjoy what he’s stolen. He just lies in it and makes sure it doesn’t go away.”

I haven’t finished reading the book; I’m about a chapter ahead of my students (I have a friend who tells me all I have to be is a tad smarter than my class), but I like to think I have a lot in common with Bilbo Baggins.

I have a side that’s been lying dormant for years, too. It actually comes from my mom and my dad, the Ayanoglou and the Lewis side. Both are great readers who did their best to surround me with the finest literature. For Pete’s sake, I lived next door to a library. It was no use, though. Reading wasn’t something I did. Reading has always been hard. Oh, I can sound the words out just fine (usually). It’s processing and understanding what I read that’s difficult. I’ve been tested for everything but “poor reading comprehension” was all that showed up.

“I’m not bright,” I told Jesse during the part where Gollum and Bilbo were giving each other riddles (none of which I understood). Jesse told me Gollum used to be a hobbit, but after he found the ring, he became the freaky, scrawny, big-eyed thing we were watching on TV. I started to cry imagining Gollum as a happy hobbit smoking a pipe and wondering about after dinner seed cakes.

“Why are you so hard on yourself?” Jesse asked putting another taquito on my plate and pouring more margarita in my glass.

“It doesn’t bother me to say it. I’m not sad,” I explained as I squeezed lime into my drink. “It takes me a while to process things, but maybe that doesn’t make me any less of a person.”

It was probably the tequila talking, but I’m looking at what I’ve underlined in my copy of The Hobbit now: “The Took side won. He suddenly felt he would go without bed and breakfast to be thought fierce.” And, “You think I am no good. I will show you…Tell me what you want done, and I will try it.” And maybe my favorite, “There is a lot more in him than you guess, and a deal more than he has any idea of himself.”

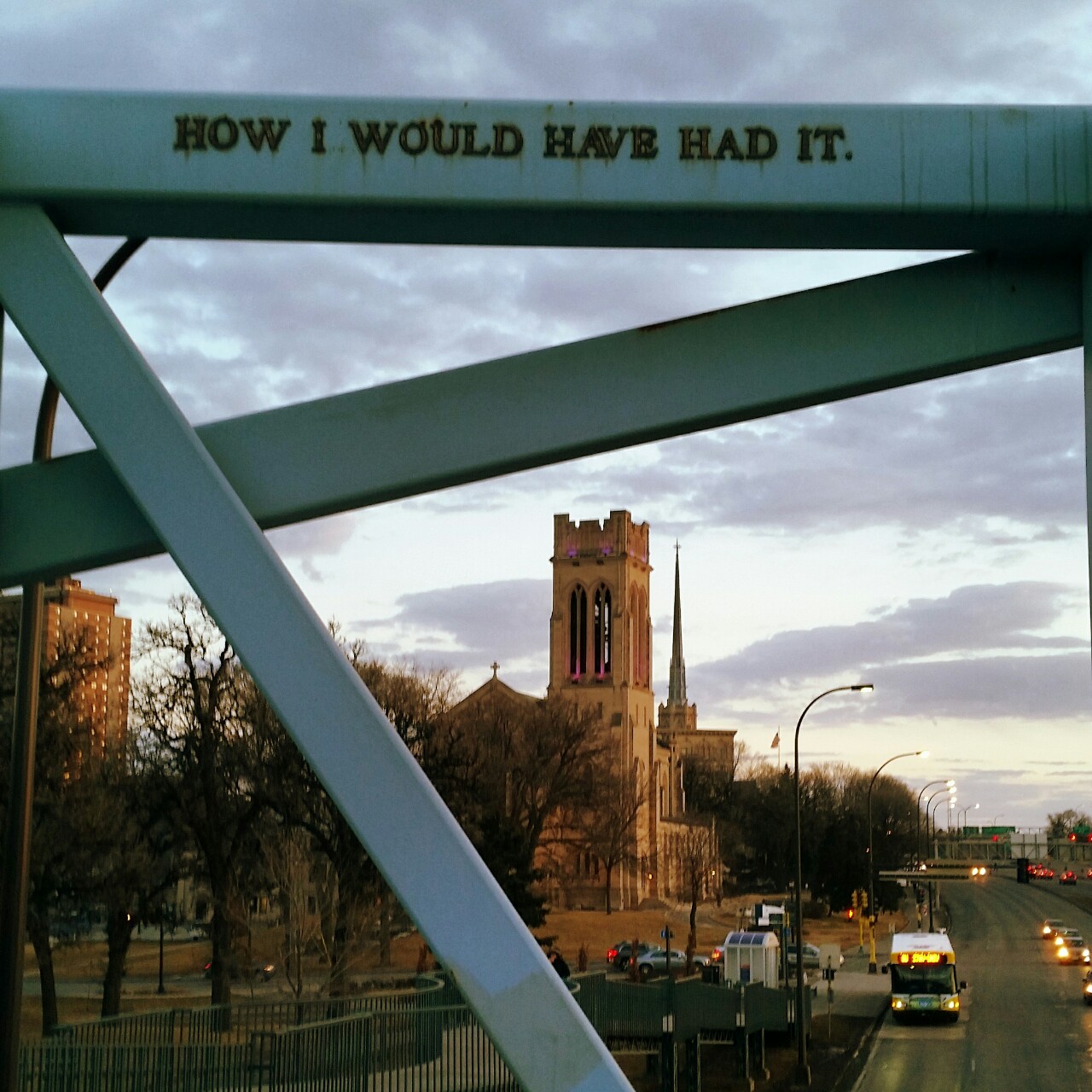

I think what I’m learning from Bilbo is that it’s not so much that you think you’d be good at something if you just had a chance. Rather, it’s trying what you don’t think you can do, and are probably afraid of, and doing it anyway because the door is open and the Lonely Mountain is waiting with a dragon who believes all that glitters must be fiercely protected.

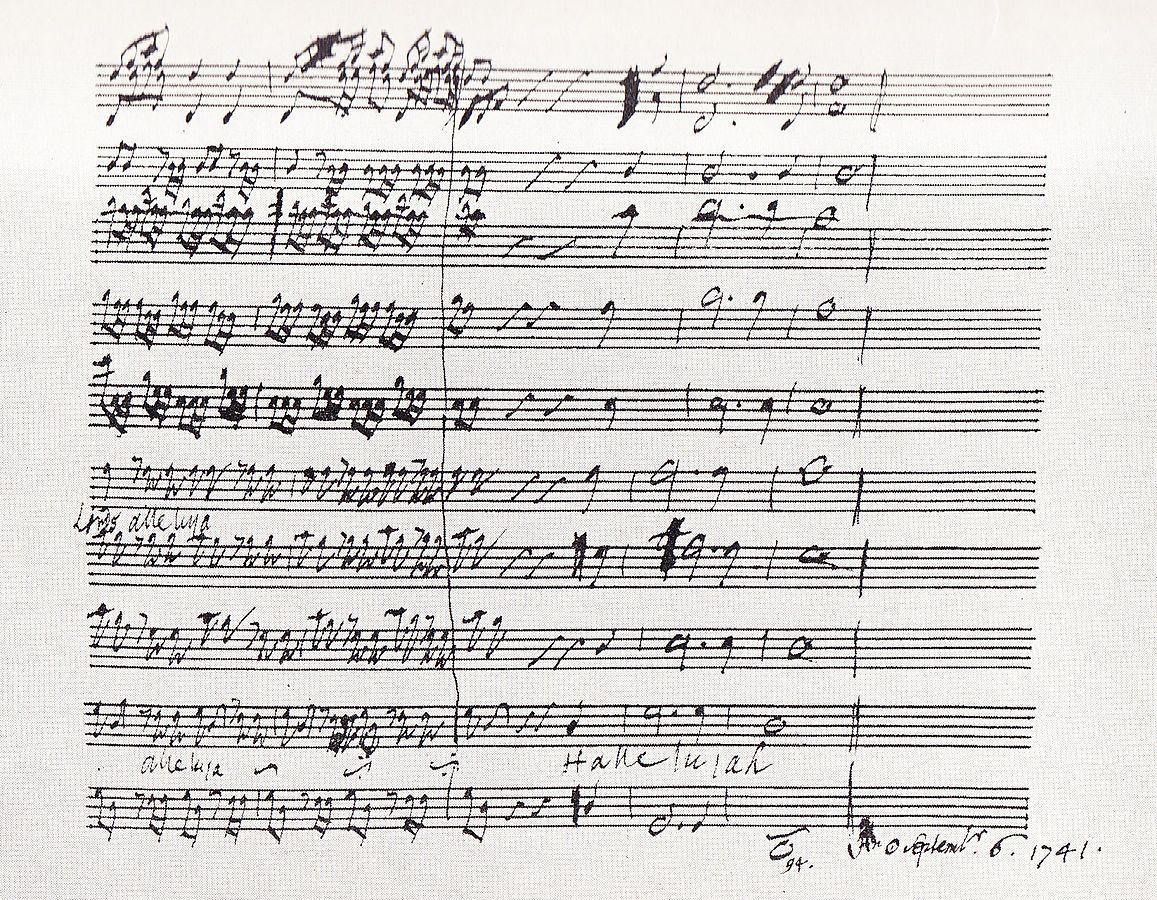

Feel it—but remember, millennia have felt it—

the sea and the beasts and the mindless stars

wrestle it down today as ever—

—

Feel it—but remember, millennia have felt it—

the sea and the beasts and the mindless stars

wrestle it down today as ever—

—

The story was told to me with flannelgraph figures that effortlessly hopped from one point on flannel to the next. Abraham figured that it was time to find a wife for his son, so he sent his servant back to the old neighborhood to find a wife who had home-training similar to his own son’s. The servant prayed that the right girl for his master’s son would make herself known by giving water to him, his team and all of their camels. The servant made several turns that led him to Rebekah. He asked her for a drink water, and she gave it to him, and offered to get water for his team and their camels until they weren’t thirsty. This was a story about asking God for help with big decisions.

The story was told to me with flannelgraph figures that effortlessly hopped from one point on flannel to the next. Abraham figured that it was time to find a wife for his son, so he sent his servant back to the old neighborhood to find a wife who had home-training similar to his own son’s. The servant prayed that the right girl for his master’s son would make herself known by giving water to him, his team and all of their camels. The servant made several turns that led him to Rebekah. He asked her for a drink water, and she gave it to him, and offered to get water for his team and their camels until they weren’t thirsty. This was a story about asking God for help with big decisions.