I first came across the idea of the “holy fool” in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s short story, “Gimpel the Fool.” The story was in a literature textbook I was using, and I didn’t have anyone to tell me what it meant. That was all the better. Even though I count it as a real flaw in my literary education that no one brought up the archetype of the holy fool, a story like Singer’s is best stumbled on alone, where the story’s very oddity throws you into vertigo.

I first came across the idea of the “holy fool” in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s short story, “Gimpel the Fool.” The story was in a literature textbook I was using, and I didn’t have anyone to tell me what it meant. That was all the better. Even though I count it as a real flaw in my literary education that no one brought up the archetype of the holy fool, a story like Singer’s is best stumbled on alone, where the story’s very oddity throws you into vertigo.

In the story, Gimpel the baker is the butt of everyone’s jokes. The biggest joke? The townspeople marry him off Hosea-like to the town prostitute, who bears him six illegitimate children. Repeatedly, Gimpel takes action to end the marriage, but instead comes to conclusions like, “What’s the good of not believing? Today it’s your wife you don’t believe; tomorrow it’s God himself you won’t take stock in.”

For a long time, I’ve struggled with the designation of Christians as “believers” for two reasons: on the one hand because it’s too wide, designating naivety and gullibility for products from Buddy Christ bobbleheads to the Precious Moments Chapel; on the other hand, because it’s too narrow, as Christians seem to be willing to believe in primarily one direction, primarily allegorical—as in, Gandalf is Jesus and the dwarves are the twelve disciples (Crap, there’s thirteen; well, Tolkien’s a word guy, must’ve miscounted).

Then, in graduate school, I came upon, well, unbelievers.

One of them, in 19th Century Nature Writing, called into question the basic ethic of the course, that we should value life because life was itself a good. “How do I know that ‘life’ is a ‘good’?” she asked. “How do I know that it’s not better that life go extinct?”

Now that’s radical, respectable doubt. She’s right: “We should value life because we should value life” is not believing; it’s tail-chasing.

In another class, I read Life of Pi with a smattering of students who were studying to be experts of story. Famously, that book spends two-hundred-plus pages recounting the trans-pacific trip of a boy on a lifeboat with a hyena, an orangutan, and a Bengal tiger named Richard Parker. Then, it performs a bait-and-switch. Investigators arrive on the scene who doubt the story. The survivor, Pi, then tells them a different story than the one we’ve been reading, a naturalistic tale in which all the characters are humans who kill each other in order to survive. The dilemma is, which story do you believe?

I take pride in the fact that I was the only one who took the first story. After all, I’m a believer. The rest? Unbelievers.

As per Singer’s story, “believing” is dangerous business: other people might quite literally shit on you, continually heap insults on you, stick you with their illegitimate children. But if you clump together with other believers under one roof and call it a church, what better place for illegitimate children?

I remember one critic on Singer’s story suggested that the Gimpels of the world get cooked in Nazi ovens. But isn’t that exactly the problem—that we blame the victim, believers, at the expense of the cynics? “Don’t believe,” the lesson goes, “or the Nazi’s will get you—we’re helpless to prevent them from rising to power and killing millions.”

Here’s the dirty little secret of a rationalist society: we revile the believer who sends all his money to the TV evangelists more than the TV evangelist; we revile Trump or Hillary supporters more than Trump or Hillary him- or herself.

I wonder if radical believing could blow up our polarized society. What happens if you believe what you see on Fox and CNN? What happens if you believe climate change and believe its doubters? What would happen if we believed everything that was said by both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton—and the green party—and the legalize marijuana party?

Maybe the holy fool explains the election season in America. Maybe that’s the only way to explain it. We turn into believers every four years.

But only partial believers. We should throw open the floodgates of belief, believe in every and all directions.

The Holy Fool archetype has roots in scripture—in Isaiah, Hosea, Ezekiel, who actually refused God’s command to cook his food over burning human dung and settled for animal scat instead.

Why not give all away all your money, marry a prostitute, support her children with your diligent work at the bakery or prophesying at the town gate?

One final sign that I’m right on this, that I’m going to become an omnivorous believer: as I wrote this—no lie—I received a “random” email form a listserv I’m a part of.

It was from Richard Parker.

My sister and I used to have picnics in our family garden and study Greek Mythology.

My sister and I used to have picnics in our family garden and study Greek Mythology.

I was in a porn film. The previous sentence is actually factually incorrect, but it’s an attention grabbing introductory line, right? Where substance doesn’t grab us, spectacle usually does the trick. I seem to recall coming across a

I was in a porn film. The previous sentence is actually factually incorrect, but it’s an attention grabbing introductory line, right? Where substance doesn’t grab us, spectacle usually does the trick. I seem to recall coming across a  I first came across the idea of the “holy fool” in

I first came across the idea of the “holy fool” in

I’m starting to get it. The spirituality of baseball. The miraculous has happened: the Cubs have won the World Series.

I’m starting to get it. The spirituality of baseball. The miraculous has happened: the Cubs have won the World Series. Out of all the treasures in the Book of Common Prayer, to me chief among them are the collects, the compendium of short and beautiful prayers, and chief among these is The Collect for Purity:

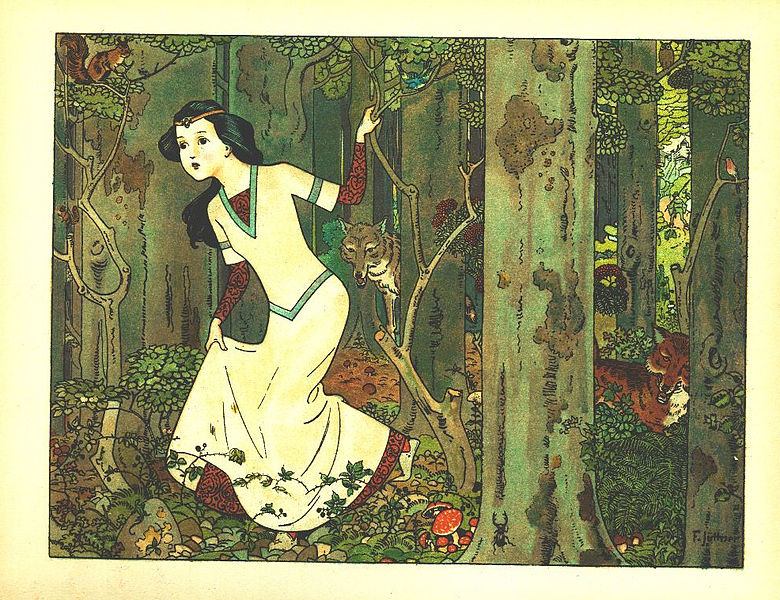

Out of all the treasures in the Book of Common Prayer, to me chief among them are the collects, the compendium of short and beautiful prayers, and chief among these is The Collect for Purity: My sister once bought a Dollar Store Snow White wig for my daughter. Three-year-old Ellie used to drag it behind her the way Linus clung to his blue blanket. She donned it at breakfast and slept in it at naptime. Day after day, wigged and rapt, she caressed the cheap dark locks with sticky toddler paws as Disney’s Snow White’s soprano pierced the thin walls of our apartment.

My sister once bought a Dollar Store Snow White wig for my daughter. Three-year-old Ellie used to drag it behind her the way Linus clung to his blue blanket. She donned it at breakfast and slept in it at naptime. Day after day, wigged and rapt, she caressed the cheap dark locks with sticky toddler paws as Disney’s Snow White’s soprano pierced the thin walls of our apartment.

It usually doesn’t happen until about mid-journey. Up till that point, the sun has been up, and you can see where you’re going. You’ve never been in this kind of car before, and you like some of the buttons and the scenery outside your window—old barns or even the edges of industrial wastes—and just the experience of being in the passenger seat and wondering where it is you’re going. The driver has a hypnotic voice and quirks that are fascinating; a tattoo runs down the side of his neck—“R-A-” something.

It usually doesn’t happen until about mid-journey. Up till that point, the sun has been up, and you can see where you’re going. You’ve never been in this kind of car before, and you like some of the buttons and the scenery outside your window—old barns or even the edges of industrial wastes—and just the experience of being in the passenger seat and wondering where it is you’re going. The driver has a hypnotic voice and quirks that are fascinating; a tattoo runs down the side of his neck—“R-A-” something. Train us Lord to fling ourselves upon the impossible

Train us Lord to fling ourselves upon the impossible

Sports have made me a superstitious person. Whenever

Sports have made me a superstitious person. Whenever  Though I am as dismayed as anyone by the current election year antics, I take comfort in remembering that bald-faced lunacy exercised in high places is nothing new. But I still have the sense that this election cycle is in a league of its own. Hopefully the bilious clouds of insanity swirling around us this fall will one day coagulate to something Americans can still recognize, once the whole thing is relegated to the history heap.

Though I am as dismayed as anyone by the current election year antics, I take comfort in remembering that bald-faced lunacy exercised in high places is nothing new. But I still have the sense that this election cycle is in a league of its own. Hopefully the bilious clouds of insanity swirling around us this fall will one day coagulate to something Americans can still recognize, once the whole thing is relegated to the history heap. A big bank just released a campaign with the following line, “A ballerina yesterday. An engineer today. Let’s get them ready for tomorrow.” When I saw it, a chuckle snuck out before I could muster up the will to be outraged. And I should be outraged. I should be offended and threaten to pull my patronage, at least, that’s what the dancers that make up a bulk of my Facebook newsfeed tell me. This advertisement is just one more national campaign that invalidates the important contribution artists make to society and discourages young people from careers in the arts, or whatever.

A big bank just released a campaign with the following line, “A ballerina yesterday. An engineer today. Let’s get them ready for tomorrow.” When I saw it, a chuckle snuck out before I could muster up the will to be outraged. And I should be outraged. I should be offended and threaten to pull my patronage, at least, that’s what the dancers that make up a bulk of my Facebook newsfeed tell me. This advertisement is just one more national campaign that invalidates the important contribution artists make to society and discourages young people from careers in the arts, or whatever.