Heavy Gleam of Domesticity: The Seven Sacraments by Abigail O’Brien

Jessica Brown

Abigail O’Brien, an Irish artist, took a decade to complete her magnanimous series of installations The Seven Sacraments. A visual meditation using different mediums—photographs, found objects, needlepoint, sculpture—this series explores the interplay of domestic life and its tangible chores with the tangibility of the sacraments, and their concrete expressions of grace. Basin, water, linen, flour, bread, fish, goblet, lilies, grapes: this list conjures items both mundane and holy—daily tasks in the realm of home as well as those made vital to the public ministry of Jesus Christ and ecclesiastical rituals.

Abigail O’Brien, an Irish artist, took a decade to complete her magnanimous series of installations The Seven Sacraments. A visual meditation using different mediums—photographs, found objects, needlepoint, sculpture—this series explores the interplay of domestic life and its tangible chores with the tangibility of the sacraments, and their concrete expressions of grace. Basin, water, linen, flour, bread, fish, goblet, lilies, grapes: this list conjures items both mundane and holy—daily tasks in the realm of home as well as those made vital to the public ministry of Jesus Christ and ecclesiastical rituals.

Photographs in O’Briens The Last Supper – Matrimony (1995) are composed so that the lit faces of women preparing for a wedding cannot help but remind us of the facial illuminations in Leonardo da Vinci’s famous painting. The richly hued lines utter a gleam of holiness in the human face and wine bottles, a wedding gown and wedding cake.

In Kitchen Pieces – Confession and Communion (1998) are photographs of bread, fish, and fruit on a black countertop again gleaming in such a way to reference Dutch and Spanish still lifes, brimming with sparkling fruit and shiny fish, themselves symbols of the sacraments. Photographs of women poised in the act of cooking are arranged in such a way to reference the beautiful comfort of Dutch interior paintings, women cooking or sewing by the glowing hearth.

What do we do, as our brains encounter such material as to make these connections between baking bread or cutting lemons with the grace of God as offered through the forgiveness of sins? I think the most uncomplicated response is one of affirmation: the sphere of domesticity is one that gleams with eternal meaning. The vita activa is not necessarily devoid of vita contemplativa, for our chores share the very tangibility that Christ treasured for his own ministry. The meaning of home can even inform how we enter the sacraments: God offers water for washing, warmth from a well-lit and enduring fire, and indeed, a place at the table set with the nourishing sustenance of wine and bread.

But there is an edge to O’Brien’s work. The Last Supper carries an undercurrent of bizarre but expected performativity, the pressure to carry out ritual in a certain way. The expression of the woman (supposedly the bride) getting her nails done is one of sober consternation. In Kitchen Pieces, the very paintings that refer to the domesticity of Dutch interiors are set in mock-up kitchens in a showroom, literally for show. The last two photographs feature a young girl in a kitchen baking bread; but the in second photo, the girl is gone, with only flour marking her place. Is this what happens when a person enters into the rituals of home-making or religion, that she loses herself?

There will always be a performative, and potentially destructive, side to rituals. The pressure to do things “right” churns within. We want our domestic tasks and the fruit of faith to be excellent, ripe, generous, lovely. And this is when the meaning of sacrament can inform how we enter ritual, domestic or religious. Sacrament is grace, and grace expects not performance but presence. Grace welcomes the transparency to admit our very inability to perform certain expectations.

The installations by Abigail O’Brien are stunning and disturbing. For me, they prompt a prayer. As we affirm the sacramental nature of daily chores—the holy gleam, as it were—may we remember to let grace affirm us, and free us from the burdensome threats of relentless perfectionism.

![By Colin Mutchler from Brooklyn, United States (Flickr) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://static1.squarespace.com/static/5898e29c725e25e7132d5a5a/58aa11bc9656ca13c4524c68/58aa12239656ca13c4525ec7/1487540771442/Mlk_quote.jpg?format=original)

![By Thesupermat (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://static1.squarespace.com/static/5898e29c725e25e7132d5a5a/58aa11bc9656ca13c4524c68/58aa12239656ca13c4525ec5/1487540771195/Pilate-Gesture.jpg?format=original) It’s so staged, so false, so politician of him. After a days-long drama of political wrangling over authority and jurisdiction that extends into the dream world of his wife, the man of power ends the debate with a gesture. Perhaps it’s his political signature: staged events to render judgments. Perhaps, backed into a corner, it’s only this time that he does it. Perhaps it’s simply functional, a way to communicate to those in the back of the crowd who can’t hear. Whatever the case, to put an end to the problem of Jesus of Nazareth, Pontius Pilate resorts to gesture: a subordinate appears on stage bearing a bowl and a towel; the man washes his hands, dries them, leaves the stage.

It’s so staged, so false, so politician of him. After a days-long drama of political wrangling over authority and jurisdiction that extends into the dream world of his wife, the man of power ends the debate with a gesture. Perhaps it’s his political signature: staged events to render judgments. Perhaps, backed into a corner, it’s only this time that he does it. Perhaps it’s simply functional, a way to communicate to those in the back of the crowd who can’t hear. Whatever the case, to put an end to the problem of Jesus of Nazareth, Pontius Pilate resorts to gesture: a subordinate appears on stage bearing a bowl and a towel; the man washes his hands, dries them, leaves the stage.

“Stick to the daily learning targets. Do not get off track.” This is one of my administrators, the one that meets with me once a week to go over my lesson plans. Daily Learning Targets are like Bible Memory Work: we are to write these words on our hearts and minds. Do not stray from these words. And it’s not that I stray, but if I were to claim a characteristic of my teaching it’s that when I begin to study and discuss a story, I tend to walk my students down a path that we didn’t know we were going to walk down.

“Stick to the daily learning targets. Do not get off track.” This is one of my administrators, the one that meets with me once a week to go over my lesson plans. Daily Learning Targets are like Bible Memory Work: we are to write these words on our hearts and minds. Do not stray from these words. And it’s not that I stray, but if I were to claim a characteristic of my teaching it’s that when I begin to study and discuss a story, I tend to walk my students down a path that we didn’t know we were going to walk down.  Four of the five years I spent selling myself to creative writing programs, I used this gem in my personal statement:

Four of the five years I spent selling myself to creative writing programs, I used this gem in my personal statement:  Nothing Gold Can Stay

Nothing Gold Can Stay The sun is snuggled still sleeping behind the mountains. He pulls their snowy peaks over his head and indulges in another hour of sleep. Not me, though. I’m awake. I’m out in public. I am caffeinated and somewhat functional. I am not necessarily in a bad mood. It's just a morning one. I am working the opening shift at the cafe. The sky is still dark.

The sun is snuggled still sleeping behind the mountains. He pulls their snowy peaks over his head and indulges in another hour of sleep. Not me, though. I’m awake. I’m out in public. I am caffeinated and somewhat functional. I am not necessarily in a bad mood. It's just a morning one. I am working the opening shift at the cafe. The sky is still dark.

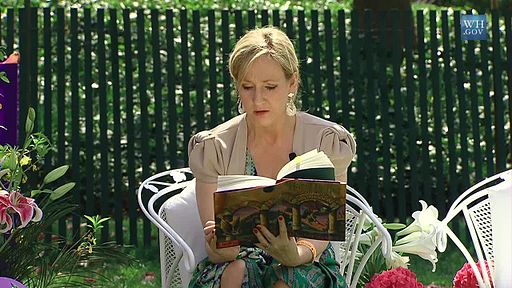

Read

Read

Where does the voice of a prayer come from? What swirling mass of the soul congeals to form syllables, words, utterances—spoken, or not, into a place we trust is more than us?

Where does the voice of a prayer come from? What swirling mass of the soul congeals to form syllables, words, utterances—spoken, or not, into a place we trust is more than us?

I worked a number of positions in television news, and the only aspect of it I really enjoyed was the news writing. The experience taught me a great deal about the kind of writer I wanted to be. And until recently, I’d forgotten I’d wanted to be the kind of writer whose stories are read aloud. There’s a power in telling stories for all to hear.

I worked a number of positions in television news, and the only aspect of it I really enjoyed was the news writing. The experience taught me a great deal about the kind of writer I wanted to be. And until recently, I’d forgotten I’d wanted to be the kind of writer whose stories are read aloud. There’s a power in telling stories for all to hear.

Oh, oh, deep water—

Oh, oh, deep water—