The Provinces of Poetry

William Coleman

Processed with VSCOcam with hb2 preset

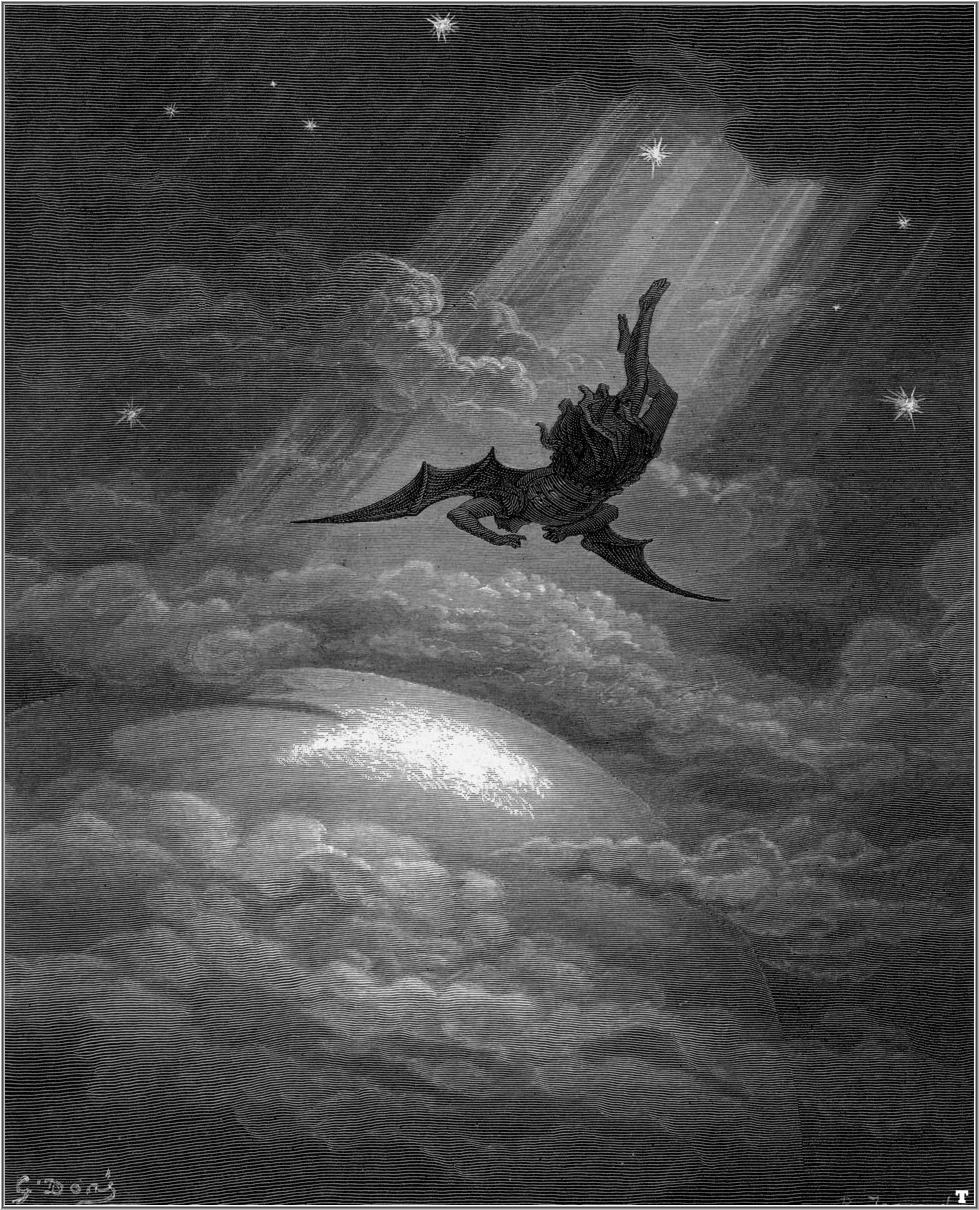

In 1983, W.S. Merwin wrote a poem called “Late Wonders.” It's a poem I return to, especially when given to wonder myself, about why poetry matters.

Though the work's over three decades old, its import—in terms of what pollutes our air and discourse, the ways in which the realm of critical and compassionate imagination has been annexed by the overweening need to be entertained—remains potent.

In Los Angeles the cars are flowing

through the white air

and the news of bombings

at Universal Studios

you can ride through an avalanche

if you have never

ridden through an avalanche

with your ticket

you can ride on a trolley

before which the Red

Sea parts

just the way it did

for Moses

you can see Los Angeles

destroyed hourly

you can watch the avenue named for somewhere else

the one on which you know you are

crumple and vanish incandescent

with a terrible cry all around you

rising from the houses and families

of everyone you have seen all day

driving shopping talking eating

it's only a movie

it's only a beam of light

The poem is a dark appraisal of what happens when destruction is treated as an occasion for consumption, when what's considered real is only that which operates under our control, when our neighbors become figures in a spectacle we've worked to pay for, and when we are automated to pass, untroubled, through waves of air bearing knowledge that would move a mind to horror. When we lose compassion and awe, the very provinces of poetry, we lose what makes us human.

The indictment could not be more complete. And yet when I read it, I feel something more akin to invigoration than defeat. I want to read it again and again, and to teach it to whomever will listen, beginning with me.

I think I feel this way because the poem itself is an act of resolution. A living, present man set it down on paper. He wrote it, and then, by God, he rewrote it. He crafted of his outrage a poem, summoned on its behalf all of his meaning-deepening and connection-finding energies. And then he mailed it across an ocean from his home in Hawaii, asking that it be published, first in a periodical, and then in a collection he called Opening the Hand, and then in his latest volume of selected poems, Migration. He worked a poem awake and sent it into our lives because in poetry, there are no lost causes. Within the integrity of poetic vision, nothing is forgotten, nothing can be cast away. Even us. For our limitations are rendered in the means of our rehabilitation: paradox and metaphor and imagery, complex ironies and rich ambiguities—the means of acts of life-sustaining attention.

Merwin's poem shows us that to exist without poetic consciousness is to be a tourist in a given world; it is to believe that all was fashioned to bring pleasure, that people exist to facilitate the satisfaction of desire, and that what happens, even when it happens right before our eyes—especially then—is not real, because nowhere feels like home. And it is to pay no mind to the condition in which we leave it.

Outside the room in which I teach is a postcard holding this quote by Christian Wiman, the former editor of Poetry Magazine:

Let us remember…that in the end we go to poetry for one reason, so that we might more fully inhabit our lives and the world in which we live them, and that if we more fully inhabit these things, we might be less apt to destroy both.

These are words I believe Merwin would affirm, for his work embodies them. They recall to me why poetry matters, why teaching poetry matters, and why writing and reading poems—even those that, in their subject matter, dispraise—is an act of urgency and hope.

I worked a number of positions in television news, and the only aspect of it I really enjoyed was the news writing. The experience taught me a great deal about the kind of writer I wanted to be. And until recently, I’d forgotten I’d wanted to be the kind of writer whose stories are read aloud. There’s a power in telling stories for all to hear.

I worked a number of positions in television news, and the only aspect of it I really enjoyed was the news writing. The experience taught me a great deal about the kind of writer I wanted to be. And until recently, I’d forgotten I’d wanted to be the kind of writer whose stories are read aloud. There’s a power in telling stories for all to hear.

Ever had one of those cool moments when, after reading about a favorite person, you suddenly receive this flash of insight? You feel one part shame for not seeing it before, but three parts satisfaction for at least coming to it eventually? Well, I should have seen this with

Ever had one of those cool moments when, after reading about a favorite person, you suddenly receive this flash of insight? You feel one part shame for not seeing it before, but three parts satisfaction for at least coming to it eventually? Well, I should have seen this with  Since my first timid slurp, rife with notes of Palmolive and expired milk, I have distrusted sour beer and all its enthusiasts. Each one has been served by a smirking bartender who addresses my splutter with a smug, “Yeah, it’s not for…everybody.”

Since my first timid slurp, rife with notes of Palmolive and expired milk, I have distrusted sour beer and all its enthusiasts. Each one has been served by a smirking bartender who addresses my splutter with a smug, “Yeah, it’s not for…everybody.”  Outside my kitchen window, a gingko tree

bursts gold, fan-shaped leaves shimmering

Outside my kitchen window, a gingko tree

bursts gold, fan-shaped leaves shimmering

I think of it like fingerprinting—fingerprinting for someone’s being-in-the-world.

I think of it like fingerprinting—fingerprinting for someone’s being-in-the-world.

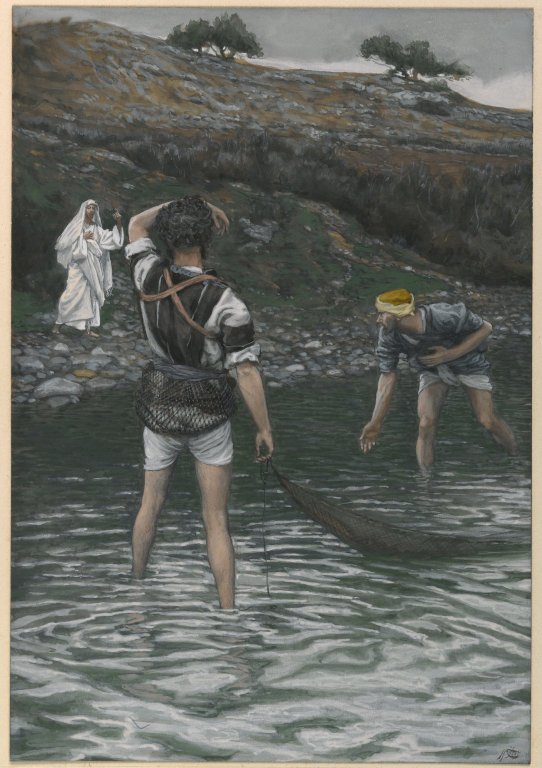

“For the mouth speaks out of that which fills the heart”

—Matthew 12.34

“For the mouth speaks out of that which fills the heart”

—Matthew 12.34 The simple answer to the question is: I’ve read enough great books to just know. But this isn’t about that answer. It’s too simple anyway—and carelessly arrogant—however satisfactory it is. Instead this is about the question I found myself contemplating after reading the opening salvo of Tim Winton’s

The simple answer to the question is: I’ve read enough great books to just know. But this isn’t about that answer. It’s too simple anyway—and carelessly arrogant—however satisfactory it is. Instead this is about the question I found myself contemplating after reading the opening salvo of Tim Winton’s

“Do you ever get used to such a place?’

She laughs then, a short bitter laugh I recognize and comprehend at once.

"Do you get used to life?" she says.

“Do you ever get used to such a place?’

She laughs then, a short bitter laugh I recognize and comprehend at once.

"Do you get used to life?" she says.

"Knowing is the responsible human struggle to rely on clues to focus on a coherent pattern and submit to its reality."

"Knowing is the responsible human struggle to rely on clues to focus on a coherent pattern and submit to its reality."  Read

Read  Last night I dreamt that I got lost again. It’s a frequent dream for me: I can’t find my car or my way home. While that type of dream may have metaphorical meaning for some people, I think it is most likely pretty literal for me. When I was a kid, sometimes I had to ask my friends at sleepovers to remind me where their bathroom was because I couldn’t quite remember their house layout and I was scared of opening the wrong door. Before smart phones and GPSs, using public transit was a complete nightmare. In addition to having the tendency of getting lost, I am also pretty good at remaining unseen. It was not that uncommon for me to be the last one sitting on the bus patiently awaiting my destination when the driver would turn around, and, with a start say, “I had no idea there was still a passenger on here!” Sometimes, I had gotten on the right bus, but on the wrong side of the street and so ended up at the other side of the city.

Last night I dreamt that I got lost again. It’s a frequent dream for me: I can’t find my car or my way home. While that type of dream may have metaphorical meaning for some people, I think it is most likely pretty literal for me. When I was a kid, sometimes I had to ask my friends at sleepovers to remind me where their bathroom was because I couldn’t quite remember their house layout and I was scared of opening the wrong door. Before smart phones and GPSs, using public transit was a complete nightmare. In addition to having the tendency of getting lost, I am also pretty good at remaining unseen. It was not that uncommon for me to be the last one sitting on the bus patiently awaiting my destination when the driver would turn around, and, with a start say, “I had no idea there was still a passenger on here!” Sometimes, I had gotten on the right bus, but on the wrong side of the street and so ended up at the other side of the city.