The Discomfort of Empathy

Jill Reid

Each fall semester, I anticipate him. I keep open a substantial space in the syllabus for one of his plays. I move through Beowulf and trek through Chaucer until I arrive at that sweet spot – Shakespeare. But however giddy I am about the bard, each year I field the same question that, when pared down to its bare bones, asks – What does dead old Shakespeare have to do with me? What does this centuries old story have to do with my field of biology or law or business?

Each fall semester, I anticipate him. I keep open a substantial space in the syllabus for one of his plays. I move through Beowulf and trek through Chaucer until I arrive at that sweet spot – Shakespeare. But however giddy I am about the bard, each year I field the same question that, when pared down to its bare bones, asks – What does dead old Shakespeare have to do with me? What does this centuries old story have to do with my field of biology or law or business?

Like any educator, I welcome the questions. They give me the opportunity to acknowledge the relationship between the words we read and the world we inhabit. Especially, the questions give me the opportunity to talk about empathy, a topic getting a lot of press in education circles and one that has recently and brilliantly been addressed by Leslie Jamison in her book, The Empathy Exams.

In my classroom, I often find that students struggle to connect the experience of discomfort to the experience of empathy. When my sophomore survey class finished Othello, some students kicked against the merit of a text they found so disturbing, so violently tragic. Despite their reluctance, the presence of their discomfort was the clearest sign that they had read the text with empathizing sensitivity. True empathy is a painstaking, uncomfortable process that resists the cheap comfort of stereotype, prejudice, and self-righteousness.

Writer James Baldwin once said, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who had ever been alive.”

Baldwin’s words suggest that we read not only for our own sake but also for the sake of others. We read not to escape from our own pain but to connect that pain to something larger than itself. And that connection occurs when a thoughtful reading snags our senses on the heartbreak or even foolishness of someone else, and we stop in our tracks and walk alongside that struggling character. Empathy does not require the reader’s agreement with a character’s choices, but it does require his understanding of that character’s plight. There is something Christ-like in becoming a reader vulnerable to the pain and hardship of a story’s characters, in extending grace “to the least of these.” Yes, characters in stories are fictional, but perhaps, if a reader can practice the act of empathy in the world of fiction, she can learn to render it even more graciously in the world of the hospital and the law firm and the boardroom.

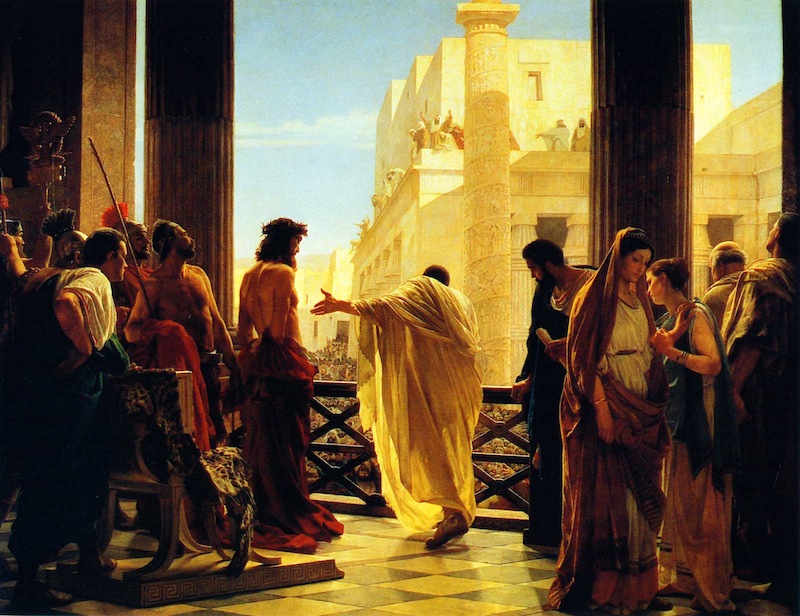

(Painting by John Edward Marin)