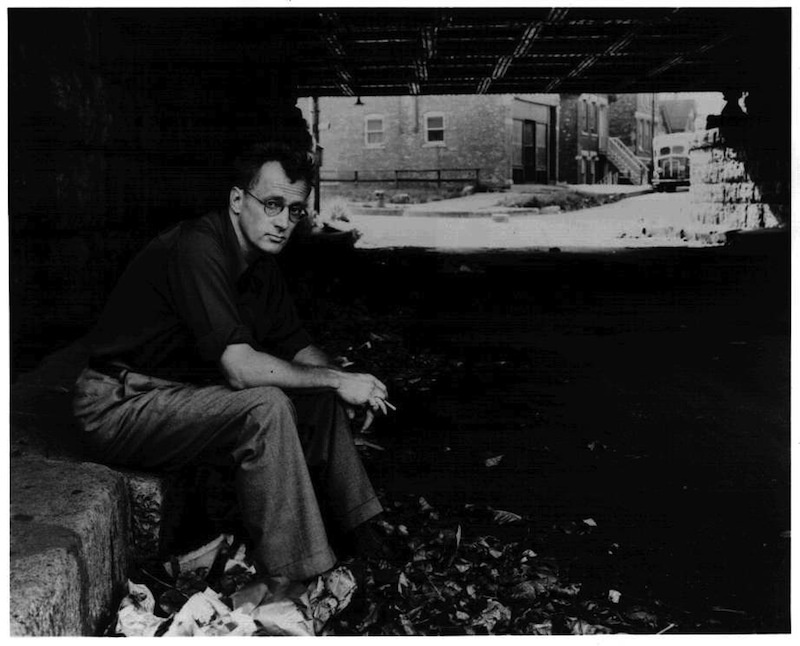

Nelson Algren

Paul Luikart

Nelson Algren spent a lot of time in homeless shelters in Chicago. This was in the 1940’s and 50’s. He wasn’t homeless, but when you read his novels and stories—especially when you realize the measures he took to get them right—you get the impression he wished that he was. He used to go to Pacific Garden Mission, a giant homeless shelter still in operation in Chicago to this day, and sit down with the drunks and down-and-outers. He’d eat dinner with them, play cards, and shoot the breeze. There’s one picture, taken by Algren’s photographer buddy Art Shay, which depicts a junkie with a hypo showing Algren how he shoots up.

All of this produced the world’s first National Book Award-winning novel in 1950—The Man With the Golden Arm. Algren’s protagonist, Frankie Machine, a struggling dope addict, is based on one of the men he used to play poker with. It is, in my opinion, the greatest novel ever written and certainly the most underrated. What makes it so good is what Algren inherently understood and then portrayed so sharply in the book: human civilization can actually only move forward at the pace of its least-of-these. That is to say, the speed of human progress is the speed at which a homeless man shambles down the sidewalk, peeking into garbage cans and begging for change.

Nelson Algren spent a lot of time in homeless shelters in Chicago. This was in the 1940’s and 50’s. He wasn’t homeless, but when you read his novels and stories—especially when you realize the measures he took to get them right—you get the impression he wished that he was. He used to go to Pacific Garden Mission, a giant homeless shelter still in operation in Chicago to this day, and sit down with the drunks and down-and-outers. He’d eat dinner with them, play cards, and shoot the breeze. There’s one picture, taken by Algren’s photographer buddy Art Shay, which depicts a junkie with a hypo showing Algren how he shoots up.

All of this produced the world’s first National Book Award-winning novel in 1950—The Man With the Golden Arm. Algren’s protagonist, Frankie Machine, a struggling dope addict, is based on one of the men he used to play poker with. It is, in my opinion, the greatest novel ever written and certainly the most underrated. What makes it so good is what Algren inherently understood and then portrayed so sharply in the book: human civilization can actually only move forward at the pace of its least-of-these. That is to say, the speed of human progress is the speed at which a homeless man shambles down the sidewalk, peeking into garbage cans and begging for change.

Where Algren gets it right—and where I get it wrong time and time again, both as a writer and as a plain old human being—is that he dared to consider how beautiful the ugly things are. There’s a Christian tune I heard with the lyric “beauty from the ashes” but suppose the beauty is actually already in the ashes?

I don’t know if Algren was Christian or not. Probably not. Besides homeless people, he also hung around with existentialists and Marxists, archenemies of the Christians back then. This was at a time when a lot of Christians figured the appropriate approach to those that Christ Himself spent so much time with was to screech the Gospel at them from afar. But judging by the way Nelson Algren lived, not to mention the content of his body of work, he acted like a Christian—the way they’re supposed to act. My prayer for myself is simply, “Dear God, make me as good of a writer and as good of a Christian as Mr. Nelson Algren. Amen.”