Imagination and Prayer

Jayne English

Imagination! who can sing thy force? Or who describe the swiftness of thy course? —Phillis Wheatley

Mechanic and machinist Arthur Pirre spent 20 years restoring his 1937 “Baby Duesenberg” Cord. He worked on details with files and wrenches and hex keys. He measured and drilled to make precisely fitting parts. Then he broadened his imagination to more abstract uses: choosing fabric and colors, sanding, painting, polishing, until the sleek curves and inventive features were remastered to their original beauty.

The poet Wallace Stevens employed different tools to craft the details of his poems: punctuation, cadence, syntax, line breaks. Like Pirre, he created with elements of abstract and imaginative thought using not just the words but the space between the words. In “The Snow Man,” he changed the familiar concepts of cold, snow, and ice into something momentous, the “nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.”

As artists, both men saw the interrelationship of details and the big picture. These tangible works of art correspond to our work in the invisible realm of prayer. Just as they labored to transform rust and words into something creatively meaningful, we labor with the Spirit to see the creation of something profound in the lives and the world around us.

Detailed prayer is straight forward. We can pray for a new roof, a humble heart, the ability to comfort a grieving friend. Details seem almost tactile compared to entering the vast, nebulous “God bless the world” prayer of a child. This is abstract prayer. Just like the element we can’t quite put a finger on in Stevens’ poems that shrouds a meaning and delivers its mystery, so the workings of prayer can’t be completely clear to our finite minds. Its abstractness is part of its power. There are no limits to who our prayers can touch because we can invoke our imaginations to include people we don’t know, complex situations beyond our grasp that we are nonetheless moved to pray about.

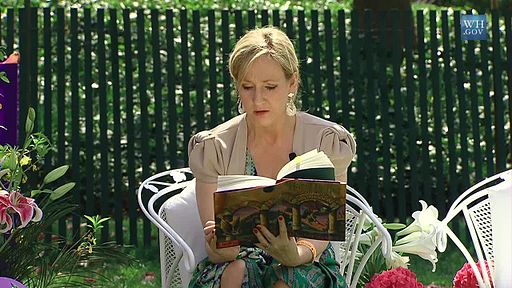

Jesus set the precedent for this kind of abstract prayer when he taught us to pray. Give us this day our daily bread and forgive us our sins both reflect the details of our day, and are easy enough (in a way) to lift up for ourselves, loved ones, and neighbors. But may your kingdom come and may your will be done are weighty and cumbersome. This is where God who gave us abstract thought and imagination invites us to use them in prayer. It’s when we can speak to God in images—picturing in our minds rather than naming with words—those we don’t know personally, extended family members of loved ones, future generations, our neighbors’ families, churches, cities, judges, presidents, countries, 7 billion people and the complex social, economic, political issues that swirl around them like clouds around the globe. The God who knows each star by name doesn’t expect us to know them, or need us to pray with an attention to detail that only his mind can grasp.

Denise Levertov muses about how God speaks to us in images in her poem Immersion:

God is surely patiently trying to immerse us in a different language, events of grace, horrifying scrolls of history and the unearned retrieval of blessings lost for ever, the poor grass returning after drought, timid, persistent. God's abstention is only from human dialects. The holy voice utters its woe and glory in myriad musics, in signs and portents.

We can speak to God in this nonlinguistic language just as the Spirit “intercedes for us with groanings too deep for words.” God invites us to pray like he invites artists to create, sometimes with detail, sometimes with abstract imagination. Pray for what you can name and what you can't. Pray with words and the spaces between words.

I worked a number of positions in television news, and the only aspect of it I really enjoyed was the news writing. The experience taught me a great deal about the kind of writer I wanted to be. And until recently, I’d forgotten I’d wanted to be the kind of writer whose stories are read aloud. There’s a power in telling stories for all to hear.

I worked a number of positions in television news, and the only aspect of it I really enjoyed was the news writing. The experience taught me a great deal about the kind of writer I wanted to be. And until recently, I’d forgotten I’d wanted to be the kind of writer whose stories are read aloud. There’s a power in telling stories for all to hear.

Oh, oh, deep water—

Oh, oh, deep water—

The wren is a big song packed into a tiny brown dart of a body with an inquisitive personality. Looking, it hops and tilts its head in that stop-action way. And it instinctively sings what is beautiful within their prodigious range of sound. One interrupted a rest between notes in a bar of music I was playing. I got up immediately, forgetting my music, and moved to the window hoping for a glimpse.

The wren is a big song packed into a tiny brown dart of a body with an inquisitive personality. Looking, it hops and tilts its head in that stop-action way. And it instinctively sings what is beautiful within their prodigious range of sound. One interrupted a rest between notes in a bar of music I was playing. I got up immediately, forgetting my music, and moved to the window hoping for a glimpse. The evening I pulled into Ann Arbor, Michigan, a rainbow appeared as I put the car in park. No kidding, it was pouring down rain and then it wasn’t and six different rays of color soared above my Mazda 5 and sailed to the Pittsfield Township water tower a few yards away. “A rainbow!” I proclaimed as I stepped out of the car, a beautiful welcome on my move to a new town.

The evening I pulled into Ann Arbor, Michigan, a rainbow appeared as I put the car in park. No kidding, it was pouring down rain and then it wasn’t and six different rays of color soared above my Mazda 5 and sailed to the Pittsfield Township water tower a few yards away. “A rainbow!” I proclaimed as I stepped out of the car, a beautiful welcome on my move to a new town. Ever had one of those cool moments when, after reading about a favorite person, you suddenly receive this flash of insight? You feel one part shame for not seeing it before, but three parts satisfaction for at least coming to it eventually? Well, I should have seen this with

Ever had one of those cool moments when, after reading about a favorite person, you suddenly receive this flash of insight? You feel one part shame for not seeing it before, but three parts satisfaction for at least coming to it eventually? Well, I should have seen this with  Since my first timid slurp, rife with notes of Palmolive and expired milk, I have distrusted sour beer and all its enthusiasts. Each one has been served by a smirking bartender who addresses my splutter with a smug, “Yeah, it’s not for…everybody.”

Since my first timid slurp, rife with notes of Palmolive and expired milk, I have distrusted sour beer and all its enthusiasts. Each one has been served by a smirking bartender who addresses my splutter with a smug, “Yeah, it’s not for…everybody.”  When

When  Outside my kitchen window, a gingko tree

bursts gold, fan-shaped leaves shimmering

Outside my kitchen window, a gingko tree

bursts gold, fan-shaped leaves shimmering

On the first day of 7th grade my history teacher asked us to write down a nickname she should use for us in class. Did she mean we could choose a nickname we wanted to be called by? An Aaron by any other name? I had felt so penned in by name at 12. It had already been egregiously mispronounced (“erin”) and misspelled (I possess a litany of incorrect name tags). Back then I didn’t know of any really admirable Aaron’s either —

On the first day of 7th grade my history teacher asked us to write down a nickname she should use for us in class. Did she mean we could choose a nickname we wanted to be called by? An Aaron by any other name? I had felt so penned in by name at 12. It had already been egregiously mispronounced (“erin”) and misspelled (I possess a litany of incorrect name tags). Back then I didn’t know of any really admirable Aaron’s either —

I pretty much went back to work. Nothing beats reality.

—

I pretty much went back to work. Nothing beats reality.

— A friend of mine who wants to put baseboards in his house was told what it takes to do good baseboard work: a thousand cuts. I can’t tell if that’s a type of hope, as even the best get to be the best through tedium not talent, or a type of torture, viz., death by a thousand maddening cuts.

A friend of mine who wants to put baseboards in his house was told what it takes to do good baseboard work: a thousand cuts. I can’t tell if that’s a type of hope, as even the best get to be the best through tedium not talent, or a type of torture, viz., death by a thousand maddening cuts.

These bodies, how they speak. How they signify, the mouth still. How their poise and rhythm scores a city sidewalk, their movements trace meanings on the moist air that separates us.

These bodies, how they speak. How they signify, the mouth still. How their poise and rhythm scores a city sidewalk, their movements trace meanings on the moist air that separates us.

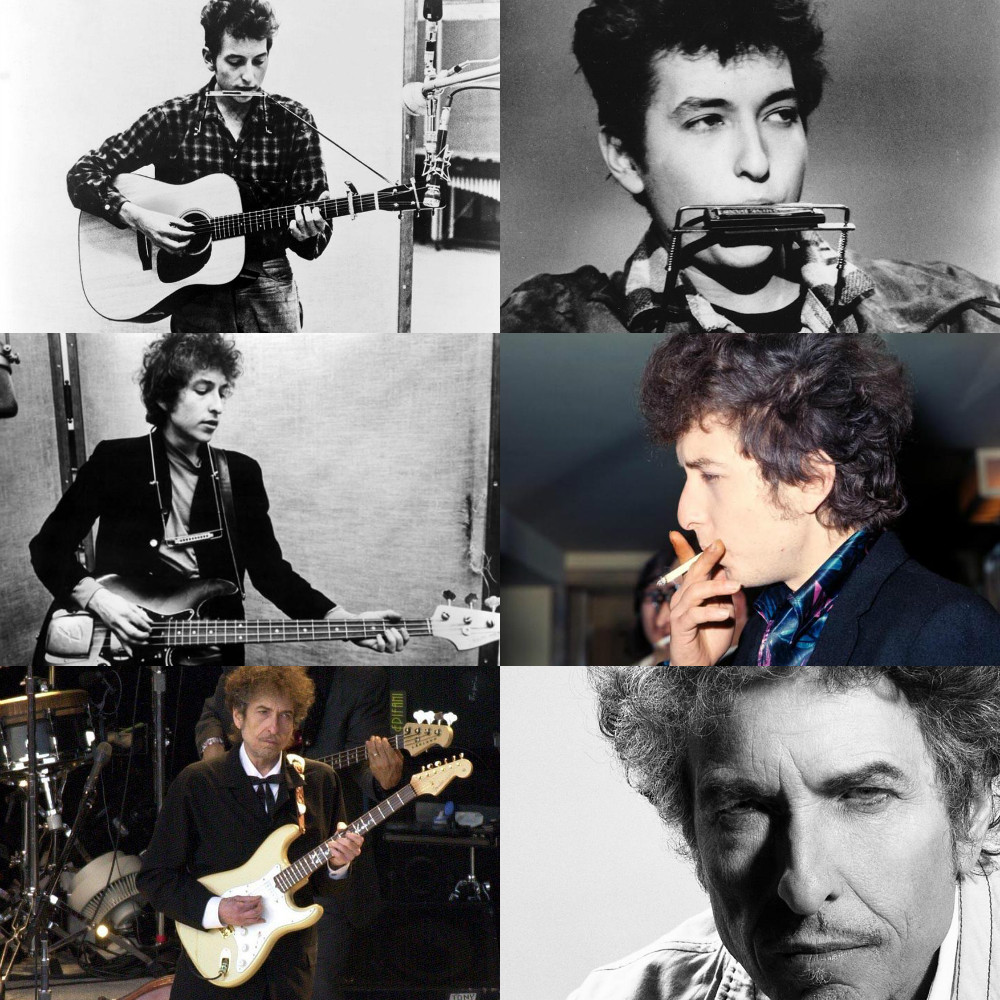

“Ah, but I was so much older then

“Ah, but I was so much older then